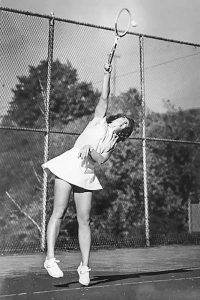

When Abbe Seldin ’78 and her parents toured the Syracuse University campus during her college search in 1974, she knew she had found her dream school. “We drove up University Avenue toward campus, and I just fell in love with it—the look, the size and all the opportunities it offered me,” she remembers. The sectionally ranked player joined the University’s women’s tennis team after enrolling in the College for Human Development—now the Falk College—where she majored in consumer studies. She excelled in her academic program and was the number one player for the team, but she worried about the financial burden four years of private college would put on her parents.

“I was an only child from New Jersey, and my parents didn’t have a lot of money,” she says. “I had looked at schools down south, but I didn’t want to be that far from home, and I didn’t want to go to a state school in New Jersey. I wanted to go to Syracuse. My parents said ‘Okay, we’ll try it for one year.’”

Finding a Lifeline

Title IX, the federal law that prohibits sex discrimination in school sports, was passed in 1972, but it had not yet been fully implemented in American high schools and colleges when Seldin was an undergraduate. There were no athletic scholarships available for female students, so with the blessing of women’s athletic director Doris Soladay, Seldin decided to approach Syracuse University Chancellor Melvin Eggers.

“All I remember is telling the Chancellor how much I loved Syracuse University and how much I wanted to stay here,” Seldin recalls. “I told him I loved playing tennis and felt I had the support of women’s athletics to get going on some Title IX issues. So I said ‘Let’s go! I need a scholarship!’”

Soon after, Seldin learned that she had become the first woman in Syracuse University history to be awarded an athletic scholarship for tennis. Scholarships were awarded in six women’s sports that year.

“I was living in Shaw Hall when I got the news,” Seldin remembers. “I got back from practice that night and found the door to my room decorated and all of my friends there to celebrate my scholarship. They knew it wasn’t just about tennis for me—it was about wanting to stay at Syracuse. Everybody was so happy for me. I’m still friends with many of those people.”

A History of Fearlessness

It wasn’t the first time Seldin had stood up to demand equal rights for herself and other athletes whose opportunities had been suppressed by sexist rules and regulations. In 1972, as a sophomore at Teaneck High School, she had sued Teaneck school officials and agencies affiliated with the State of New Jersey over a rule that barred her from trying out for the varsity boys’ tennis team. There was no girls’ team at her school and the coach of the boys’ team had publicly announced that he would welcome her participation.

It wasn’t the first time Seldin had stood up to demand equal rights for herself and other athletes whose opportunities had been suppressed by sexist rules and regulations. In 1972, as a sophomore at Teaneck High School, she had sued Teaneck school officials and agencies affiliated with the State of New Jersey over a rule that barred her from trying out for the varsity boys’ tennis team. There was no girls’ team at her school and the coach of the boys’ team had publicly announced that he would welcome her participation.

A Rutgers University law professor had recently co-founded the American Civil Liberties Union’s Women’s Rights Project, which tackled gender discrimination cases. Seldin’s case was one she was eager to take on.

The lawyer’s name was Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

“I remember many phone conversations with Ginsburg,” Seldin says. “I was only 15 but I wasn’t afraid to talk to her. She was such a lovely, soft-spoken person, and I could tell her how I really felt. I said I was a tournament player and I just wanted the experience of playing on a team before I went to college. Her main concern was that this was going to be a long-term fight, and she wanted to make sure I was in it for the duration.”

No Regrets

The case was delayed and eventually dropped after the state began to allow girls to try out for boys’ teams. Seldin did join the boys’ team, but by then a new coach had taken over, and she was treated with such disrespect and cruelty in practices that she quit before she ever played in a game. “I have no regrets about it at all,” Seldin says. “I still feel it was a victory for me, because other girls got to benefit from it. And I benefitted from it so much in life. It gave me the courage to approach the Chancellor when I got to Syracuse, and it helped me gain the confidence I needed to succeed in my sales career after college.”

In 2011, Seldin was invited to an ACLU event honoring Ginsburg. The justice, who had been appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1993, was unable to attend, but the experience held great meaning for Seldin. “Ginsburg represented me when she was just 39 years old—a really busy time in her life,” Seldin says. “But she quietly worked every day for those who had been discriminated against—gay couples, transgender people, adopted children and racial minorities. When I learned that she had died, I was so sad, and I feared for our country.”

Following Ginsburg’s death in September, Seldin was contacted by news organizations that wanted to showcase lives that had been changed by Ginsburg’s commitment to equality. Features about Seldin appeared in The New York Times, USA Today, The NJ Record, Cape Cod Times, Provincetown Banner and Provincetown Independent. “A lot of the successes in my life came from the lessons I learned from that,” Seldin told the Times.

Orange-Shaded Memories

Seldin considers her Syracuse University experience to be one her biggest successes. “I was playing tennis in the spring and the fall, I joined Sigma Delta Tau, and I had two jobs: checking IDs and directing people at the door of the Women’s Building and teaching tennis to kids in the Syracuse area,” she says. “I was developing my mind, learning teamwork and making friends. And I was in a beautiful place, physically and emotionally.”

After graduation, Seldin taught tennis for two years and was certified by the United States Professional Tennis Association. She then put her consumer studies degree to work with a career in consumer product sales followed by promotional marketing tool sales. “I loved it, but I was born too soon. If I were a Syracuse University student now, I’d be majoring in sport management,” she says, referring to the popular Falk College major that was introduced in 2005. “My energy would have been great in that profession. You have to know the commitment it takes to be an athlete.”

After 25 years of living in New York and flying all over the country for work, Seldin moved to Cape Cod, where she lives in Wellfleet with Farny Schneider, her partner of 37 years. She enjoys her work with MLS Property Information Network (a multiple listing service), through which she engages with customers and sells the service on Cape Cod so that their listings are shared with more than 43,000 real estate professionals across New England.

Two titanium knee replacements have made it possible for Seldin to play tennis regularly, and she looks forward to a post-COVID-19 visit to the campus that shaped so much of her life. “You know how you sometimes just want to go back to a happy time in your life? Syracuse is the place I go back to for good, comforting thoughts,” she muses. “It was just the best time in my life.”

An SU Story by Mary Beth Horsington originally published on November 5, 2020