For Raven Campbell, who grew up in Jamaica and moved to the United States when she was 14, the journey to her chosen career path has at times felt just as long and daunting.

But in conversations with her family and Falk College advisor, Colleen Cameron, and through out-of-classroom experiences such as her observership this past spring at a hospital in Kingston, Campbell has transformed her passion for working with children into her career goals of becoming a child life specialist and then a developmental pediatrician.

While pediatricians offer general primary care services to children, developmental pediatricians assist in specific difficulties, struggles, or deficiencies in the growth and development of a child.

“I’ve always had a love for children and felt a spark when I was around them,” Campbell says. “But career-wise, I didn’t know what I was going to do.

“I had my first class with Professor Cameron, and she was talking about child life, and I thought that was something I wanted to do,” Campbell continues. “As time passed, I wanted to do more with that and this spring in Jamaica I met a developmental pediatrician and learned that’s something I’m interested in doing while also getting my child life specialist certification.”

Cameron, a professor of practice in the Department of Human Development and Family Science at Falk College, says Campbell’s child life coursework has provided a foundation that will benefit her as a developmental pediatrician because the curriculum focuses on the impact of illness, injury, trauma, and hospitalization on human development.

“Raven’s ambition to pursue dual credentials makes sense to me because she’s someone who wants to leave no stone unturned and is deeply committed to providing exceptional care to children and families,” Cameron says. “It takes a lot of work to become certified, but she sees the value in the knowledge, skills, and abilities of child life specialists and how having that skillset can take you far in meeting the needs of children, youth, families, and communities.”

‘Children Gravitate Toward Her’

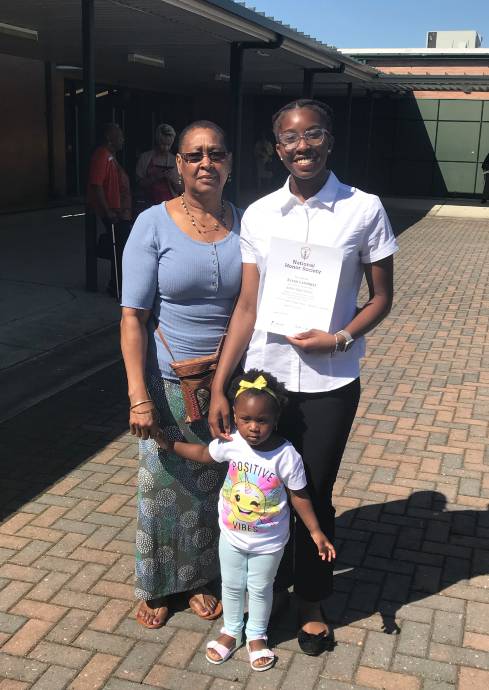

Born in Brooklyn, Campbell moved to Kingston with her family when she was a baby. She grew up in a house that centered on children and education as her mother, Pauladene Steele, is in her 23rd year as a teacher, Coordinator of the International Baccalaureate Diploma Program, and now Vice Principal at the Hillel Academy, a private international school in Kingston.

“I saw very early that how she interacted with children really stood out,” Steele says. “I found it unique that children–ones she knew and ones she didn’t know–would easily gravitate toward her and it became more pronounced as she started to interact in Sunday School at church.

“She had this calming effect where children were involved,” Steele adds. “And she could take on the identity of an older one, a little one, a baby; she had that fluidity in terms of engaging and interacting with all children.”

When she was 14, Campbell moved to the United States to live with her uncle (Steele’s brother) in Virginia. Steele wanted her daughter to have a U.S. education, and Campbell spent four years at Bethel High School in Hampton, Virgina.

During that time, Campbell’s aunt had a baby, Mialani, and Campbell is proud to say that she helped raise her. While enjoying the time with her cousin, Campbell started to become curious about child development and the cultural differences between the United States and Jamaica.

“In Jamaican culture, it’s normal for conversations you have with a child to be more like the conversations you have with adults; it’s not baby talk,’” Campbell says. “With food as well; people here tend to wean their kids into solid foods, but Jamaican people give babies various kinds of foods from an early age. I had a different perspective than other people because I grew up in a Jamaican family and things were so different.”

When she was a senior in high school, which was also the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, Campbell became ill with sepsis and had to be hospitalized. Sepsis is a serious condition that occurs when the body’s immune system has an extreme response to an infection.

“After the care she received, she said, ‘Mom, I really want to work in a hospital. I don’t want to be a medical doctor, but I want to work in a hospital and work with children,’” Steele says. “She thought a big part of her recovery was because of the attention and care she received from the different practitioners who helped her, and she wanted to do just that.”

‘Feeling the Vibe’

Campbell’s uncle in Virginia had wanted to attend Syracuse University but ended up at Florida International University. But his fondness for Syracuse stuck with Campbell, who was accepted and enrolled as a freshman in the fall of 2020.

As she explored professions that focus on children, Campbell discovered Falk College and discussed her career goals with Falk academic counselor Malissa Monaghan, who recommended she take courses in human development and family science (HDFS).

“HDFS, in my opinion, is the best way to better understand underlying processes that impact health and wellness across cultural communities, contexts, and developmental stages,” says Cameron, Campbell’s Falk advisor. “Our degree provides an exceptional foundation for anyone who sees themselves providing healthcare services for individuals across the developmental continuum.”

As Campbell says, she “started to feel the vibe” of HDFS and met with Cameron, who says she always starts conversations with students by asking them to first identify and articulate what they are interested in before talking about specific career titles.

“I want to know what skills and abilities they hope to obtain, how do they envision their future, and in what settings?” Cameron says. “From there, we can begin to think about co-curricular experiences, and I have a ‘go-to’ list of opportunities that students can pursue each year of their undergraduate experience. Then, students can begin to see the careers and fields that link with their interests.”

In that first meeting, Cameron introduced information about the child life specialist curriculum, which was the first curriculum in the world to be endorsed by the Association of Child Life Professionals. With her child life classes, Campbell was starting to feel the spark that she felt around children when she was growing up.

Following Cameron’s advice, Campbell sought experiences outside of the classroom. She went on the HDFS immersion trip to New York City last fall, volunteered at Upstate University Hospital in Syracuse in the spring, and interned at the Bernice M. Wright School on South Campus in the spring. In May 2022, she attended the Association of Child Life Professionals’ Child Life Conference in National Harbor, Maryland, where “she was a rock star,” Cameron says.

But perhaps Campbell’s most life-changing experience would occur this past spring when she returned home to spend three weeks at University Hospital of the West Indies in Jamaica.

‘Brings Joy to My Heart’

Campbell’s mother, Steele, has a friend, Professor of Pediatrics and Infectious Diseases Celia Christie, who is a Senior Consultant Pediatrician for the hospital and is “very passionate about Raven’s development and progress,” Steele says. Through this connection, Campbell spent three weeks in June under the supervision of developmental pediatrician Dr. Andrea Garbutt.

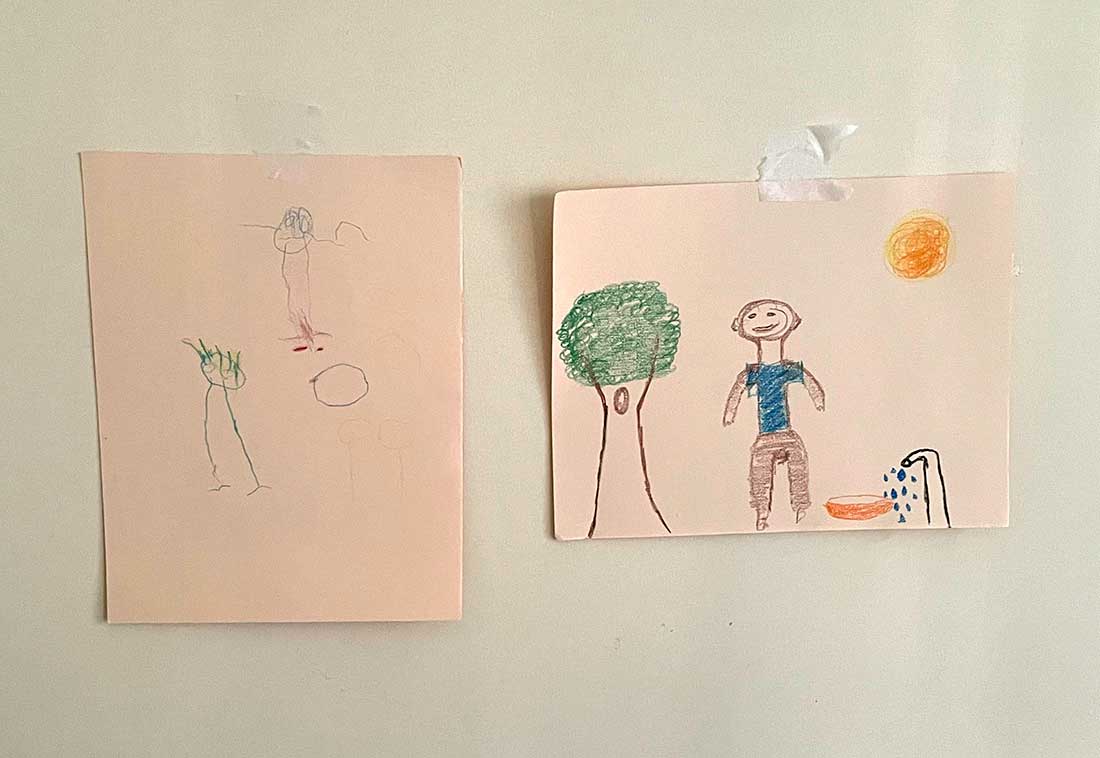

Campbell spent her time observing–and speaking with–doctors, nurses, teachers, and social workers about the psychosocial care of children and families at the hospital. Jamaica does not utilize child life specialists, and Campbell’s “final exam” was a 22-page paper explaining why the hospital should employ a child life specialist who could help children and families navigate the process of illness, injury, disability, trauma, and hospitalization.

To Campbell, the reasons for having a child life specialist were clear. The hospital didn’t have toys or a playroom for children, many of whom were oncology patients who were placed in an adult ward and couldn’t be moved. That first night, Campbell and her mother purchased toys, coloring books, crayons, and other supplies that she could provide to the children to take their minds off their diagnosis and “allow them to be kids,” Campbell says.

“Their parents may be far away, or working to pay for hospital bills, and these children don’t have anyone around except for the doctors and nurses who are busy with several patients,” Campbell says. “So, to have someone who’s there for them, advocating for them, listening to them, and playing with them, that was all they needed.

“And even if I wasn’t playing and I was just sitting there watching them, they were coming around and laughing,” she continues. “I heard the joy, and it scared me that if I left it wasn’t going to happen anymore.”

While observing Garbutt, Campbell realized that being in a hospital setting as a developmental pediatrician would be the best path for her to take her child life skills to the next level.

“It’s opened my eyes to the fact that sometimes issues go undiagnosed, and I would want to be the person to diagnose it, saying this is what I observed, this might be what’s wrong, and this is how I can help,” Campbell says.

As with the journey from Jamaica to Syracuse, it won’t be easy. A double major in psychology and human development and family science who’s on track to graduate in May, Campbell will need seven more years of education, including four in medical school, to become a developmental pediatrician.

But when she thinks of her future, Campbell says she often refers to a quote attributed to the Chinese philosopher Confucius: “Choose a job you love, and you’ll never work a day in your life.”

“In that hospital setting, it was important to me that they were getting back to being kids rather than patients,” Campbell says. “If I can be part of that equation, that’s something that brings joy to my heart.”