As a master’s student years ago, Lenny Grant did community outreach for his college’s writing center, working with a group of widows aged 75 to 96 as they wrote about their life experiences. Little did he know that he’d take lessons from them, have one of the most rewarding experiences of his career and gain inspiration for future research.

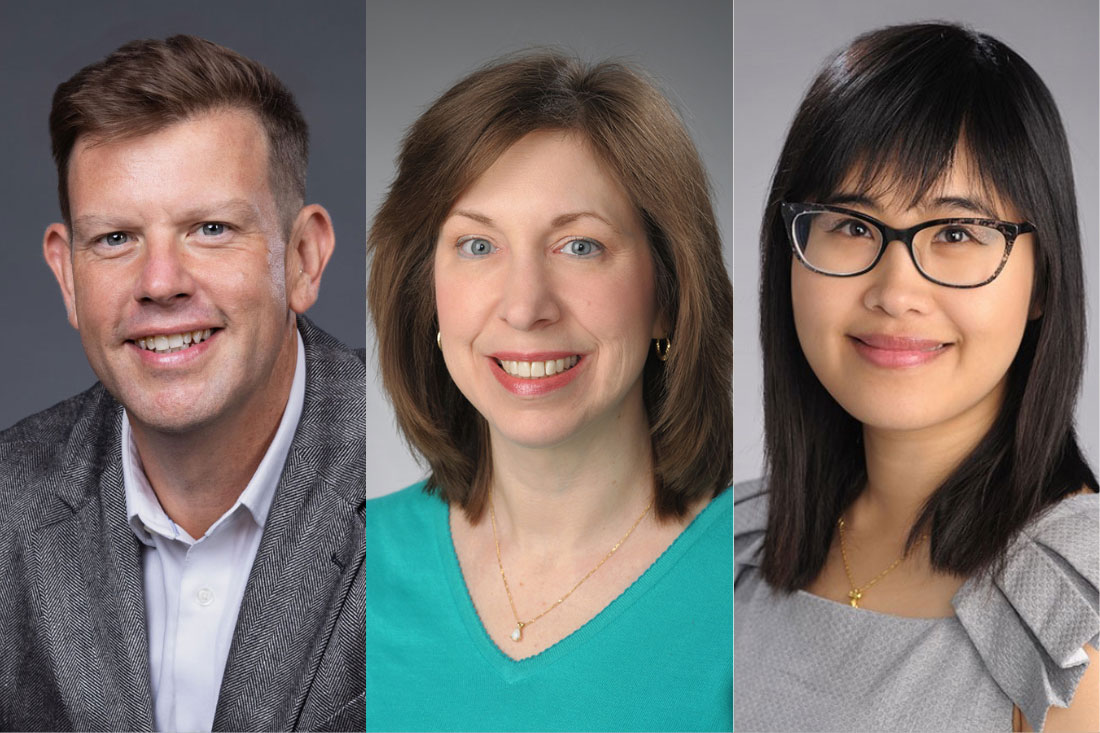

Those workshops provided Grant, now an assistant professor in the College of Arts and Sciences in the Department of Writing Studies, Rhetoric and Composition, with a realization of how the writing process can improve mental and physical health.

“Amazing things happened,” Grant says. “The women started coming to the sessions every week reporting better health outcomes. They felt better, had greater mental clarity and experienced better connectivity to their families and to each other. Witnessing their transformation flabbergasted me.”

CUSE Grant Expansion

More recently Grant hosted a series of virtual writing workshops for Syracuse-area social workers to test if expressive writing—writing to convey a person’s thoughts and feelings about difficult events and issues—could help social workers boost their own mental and physical resilience.

The pilot Resilience Writing Project showed promise, so he applied for and received funds to expand the program online. He and his research team started work this summer using a Collaboration for Unprecedented Success and Excellence (CUSE) grant for $22,000.

Learning whether the writing style provides a useful intervention to help social workers and mental health professionals build emotional and physical resilience is important, Grant says. Those professionals can experience “compassion fatigue”—secondary traumatic psychological stress—as a residual impact of their work helping others overcome trauma.

“Every day, social workers help people who are having the worst days of their lives. They provide invaluable support to our community members in hospitals, human services agencies, private practice and other settings. As they do their jobs, they are exposed to the traumas and catastrophic experiences of those they help. While busy caring for others, social workers sometimes don’t have the time to care for themselves or there’s limited infrastructure in place to help them do that,” he says.

Increased Need

The last few years of high stress, including the COVID-19 pandemic, has created a crisis in the mental health care professions and threatens to undermine an already overwhelmed mental health infrastructure, Grant says.

Co-investigator Tracey Marchese, professor of practice in the School of Social Work in Falk College and an expert in trauma practice and education as well as a 30-year mental health practitioner, agrees. “This is an unprecedented time,” Marchese says. “What we’ve seen, particularly since COVID, is that in the process of trying to help their clients, clinical mental health practitioners are at the same time experiencing the same concerns and anxieties as their clients.”

Recruiting Participants

Through the summer, work was done to develop scripts, videotape instructions, create a website and put data collection and evaluation tools in place. Participants are now being recruited. The team wants to enroll 100 licensed or provisionally licensed professionals working in mental health counseling, psychology, marriage and family therapy, and social workers. The pool includes Syracuse University partner agencies and professionals from an area encompassing the North Country, to Rochester, to Utica, to Northeast Pennsylvania—areas all experiencing heightened needs for mental health workers.

Six Short Exercises

To engage in the program, participants go to the website, watch a short video, view a sample piece of writing and then are prompted to complete the exercise. The series of six exercises use expressive writing techniques that encourage deep engagement with the traumatic issue and related emotions. Writers are asked to create a narrative of a traumatic experience, reframe the narrative in the third person, develop an imaginary dialogue, write a letter of gratitude, devise a mindfulness poem and outline a future retrospective.

The program is self-paced and accessible online anytime. Modules are condensed to take no more than 20 minutes each. The idea is that harried mental health workers will be more willing to engage with expressive writing if sessions are offered in short form on a virtual platform that they can access at their convenience.

Also a co-investigator on the project is Xiafei Wang, assistant professor in the Falk College’s School of Social Work, a mixed-methods researcher and educator in program evaluation whose expertise is evaluation design and data analysis with a specialty in trauma and behavioral health.

Wang will assess the written material and its linguistics using qualitative content analyses and quantitative data analysis based on repeated-measure design. The combination of methods will show the usefulness of the results of the study in regard to the healing power of writing, Wang says. The team may also do some in-person interviews to gain detail about the participant experience.

Why Does It Help?

What is it about the expressive writing form that seems to help people? “We have theories about the mechanisms behind the health benefits of expressive writing, but we are still seeking concrete answers,” Grant says. He has a hypothesis, though: People who experience traumas or catastrophic events can feel those things don’t make sense because they become overwhelmed emotionally and physically.

Meanwhile, the writing process is slow and linear, requiring a person to slow down, look in their mind’s eye and create a narrative about the experience, he says. “I think it’s in that process that the healing happens. Traumatic events often leave us with a whirlwind of unresolved emotions, images and thoughts. The expressive writing process helps us to examine those feelings and memories closely. Through writing, we can take something that didn’t make sense before and make meaning of it.”

Marchese says that if preliminary research shows the program is helpful it could be broadened to all mental health professionals in all disciplines and put into use industrywide. “If this program starts mental health practitioners in positive self-care practices, and we find ways to get people really invested in their own mental health and building their resilience so they can be better for the people they serve, that would be fantastic,” she says.

Just as that long-ago widows writing workshop produced positive results, Grant is hopeful the virtual resilience platform will be a gift to the mental health care community who are necessarily in high demand. “That demand has consequences mental health professionals may not be processing because while they are processing other people’s issues,” Grant says. “They sometimes don’t get the chance to take care of themselves. This is an invitation to do that and it’s something they can do from the comfort of their office in their own time and at their own pace.”

~ A SU News story by Diane Stirling originally published on Tuesday, October 4, 2022.