Instead of wallowing in what could have potentially been the lowest moment of her life, Kathrine Switzer ’68, G’72, H’18 used the adversity she overcame during her historic run at the Boston Marathon as fuel to inspire women around the world.

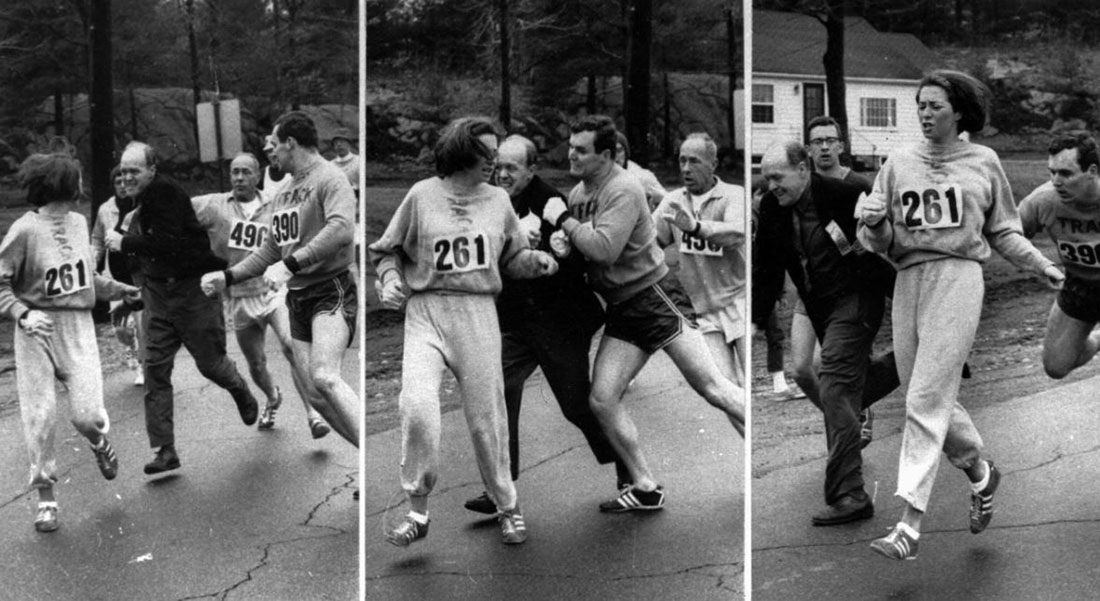

Switzer, who in 1967 became the first woman to officially run and finish the Boston Marathon when she entered as K.V. Switzer using bib number 261, contended not only with the grueling course and frigid race conditions, but also a physical challenge from race director Jock Semple. Around mile four, Semple leapt out of the photographers’ press truck and headed straight for Switzer and her contingent of runners from Syracuse University.

As Semple tried to rip Switzer’s bib off the front and back of her grey Syracuse track sweatshirt, Switzer was frightened. Her coach, Arnie Briggs, the University’s mailman and a veteran runner at the Boston Marathon, tried to convince Semple that Switzer belonged in the race, to no avail. Only after Switzer’s boyfriend, Tom Miller, a member of the Orange football and track and field teams, blocked Semple, was Switzer free to continue chasing down her pursuit of history.

In that moment, Switzer followed Briggs’ advice to run like hell, driven to prove Semple and the other doubters wrong by finishing the race. She hasn’t stopped running with a purpose since.

’Cuse Conversations: How Trailblazer Kathrine Switzer ’68, G’72, H’18 Uses Using Running to Motivate, Inspire Women Worldwide

“As I was running, I realized that if these women had the opportunity, just the opportunity, that’s all they needed. And by the time I finished the race I said, ‘I’m going to prove myself, play by their rules and then change those rules,’” says Switzer, an emeritus member of the Falk College of Sport and Human Dynamics’ Department of Sport Management Advisory Council.

“From the worst things can come the best things and that’s what I tell students whenever I speak to classes. If something is wrong, there’s an opportunity to change it, and we can then reverse it. When you’re training for a marathon, you’re out there for hours by yourself. I loved to use that time to take on a problem and solve it,” says Switzer, who earned bachelor’s degrees in journalism from the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications and English from the College of Arts and Sciences, and a master’s degree in public relations from the Newhouse School.

After her triumph in Boston, Switzer would complete more than 40 marathons, including winning the New York City Marathon in 1974, and she was instrumental in getting the women’s marathon included in the Summer Olympics. Switzer’s global nonprofit, 261 Fearless (an homage to her Boston race bib), has helped thousands of women discover their potential through the creation of local running clubs, educational programs, communication platforms and social running events.

On this “’Cuse Conversation,” Switzer discusses making history as the first woman to run the Boston Marathon, why she’s never stopped advocating for the inclusion of women in sports and what it means to be a proud alumna whose running career was launched as a student on campus.

How did you use the Boston Marathon experience to create more running opportunities for women?

I was raised by parents who said you know right from wrong, so always go for what’s right. I knew it was going to be time-consuming, but I knew it was important to both correct the error the establishment had made, but more than that, I wanted women to know how great you can feel when you’re running. When I was running, I felt empowered. I felt like I could overcome anything. Running is naturally empowering, it’s a super endorphin high, and I wanted women to experience that.

One of the issues I wanted to solve was getting the women’s marathon into the Summer Olympics. It came down to opportunities and I wanted to create these opportunities, so [once I was working for Avon Cosmetics] I created the Avon International Running Circuit, a series of races around the world that are for women only, where we could make every woman feel welcome and treat her like a hero.

Eventually, we had 400 races in 27 countries for over a million women around the world. We had the participation, we had the sponsorships, we had the media coverage and we had the international representation. In 1981, by a vote of nine to one, women’s marathon was voted into the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, California. That was an incredible feeling.

What has running given you?

Running has given me just about everything. It’s given me my religion, my husband, travel opportunities, my health and wellness, but the biggest thing it has given me is this perspective on myself, this empowerment and belief in myself that I can do whatever I set out to accomplish.

What kind of impact has 261 Fearless had in empowering and lifting up other women through running?

We’ve already proved that, regardless of your age, your ability or your background, if you get out there and put one foot in front of the other, you’re going to become empowered. If you want to lift a woman up, show her how to run.

We need to do it at the grassroots level and invite women around the world to have a jog or a walk with one of our more than 500 trained coaches. We’re working village by village, city by city, country by country to spread the word on the life-changing benefits of running, and we’ve worked with nearly 7,000 women in 14 countries and five continents so far. 261 was perfect for this mission. It became a number that means being fearless in the face of adversity. People have told me that 261 Fearless has changed their lives and that they’re taking courage from what I did.

Note: This conversation was edited for brevity and clarity.

John Boccacino:

Hello and welcome back to the ‘Cuse Conversations Podcast. I’m John Boccacino, senior internal communications specialist at Syracuse University.

Kathrine Switzer:

I realized that, if these women had the opportunity, just the opportunity, that’s all they needed. And by the time I finished the race, I said, “Okay, I’m going to be a better athlete, get my credibility together here, prove myself, play by their rules, whatever they are, and change those rules.” I wanted women to know how great you can feel when you’re running. As long as I ran, I felt empowered, I felt like I could overcome anything. And it is, running is naturally empowering, it’s a super, super endorphin high and so it’s very, very beneficial for thinking and clarity and I did a hell of a lot of thinking. When you’re trainingfor a marathon, you’re out there for hours alone and you can take on a problem and solve it.

John Boccacino:

Well, our guest on this episode of the ‘Cuse Conversations podcast is Kathrine Switzer, the inspirational and trailblazing rnne r who made history as the first woman to officially run the Boston Marathon in 1967 but her story is so much more involved than just that date at the Boston Marathon. Kathrine has made a habit out of breaking barriers and, because of her courage in the face of adversity, millions of women have become empowered through the simple act of running. Kathrine has completed more than 40 marathons in her career, including winning the New York City Marathon in 1974.

In 2015, along with four of her friends, Kathrine launched 261 Fearless, a global non-profit that empowers women through running, helping thousands of women around the world discover their self-worth and their potential through customized education and running opportunities. The 261 is an homage to the bib number that Kathrine sported when she successfully ran the 1967 Boston Marathon as K.V. Switzer. Kathrine, it’s an impressive resume you’ve got, I appreciate you making the time, thanks for joining us.

Kathrine Switzer:

Thank you, John, for having me here. I’m an orange girl through and through and it’s wonderful to be back on campus and talking to you.

John Boccacino:

Really, you can tell through and through that you bleed orange and we’ll go through the whole arc, your running career started here at Syracuse. But I know it can be difficult but I do want to go back to that day, the day that has defined and launched your brand and your reputation as being someone who supports and empowers women through running. What was that like with the Boston Marathon, the emotions? What was going through your mind as you and your cross-country coach, and I want to call him a coach because Arnie Briggs was a volunteer but he really played a key role that we’ll get to in your career here, what was going through your mind heading down to Boston?

Kathrine Switzer:

Well, I’ve got to back up, John, honestly, because the story actually began out on the Drumlins Golf Course. I had gone in to see the track coach a couple of days before and asked if I could run on the men’s cross-country team because, at my previous college, I was recruited to run the mile for the men so that they could get points and they had no problems with it. And when I came to Syracuse and I asked the coach since there was no women’s sports teams in those days-

John Boccacino:

Before Title IX, of course.

Kathrine Switzer:

Yeah. But not just running, there was no field hockey, no lacrosse, nothing, nothing. So, I said, “Okay, I’m going to run,” so I asked the coach if I could run on the men’s cross-country team. And he said, “No, it’s against NCAA rules but you can come out and work out with the team if you’d like to.” And I said, “Well, fine, Coach, where do you go?” and he said, “Drumlins,” I said, “Okay, well, I’ll see you tomorrow.” And just before I closed the door, I heard him burst out laughing and say to his colleagues, “I think I got rid of that one.” I was so upset because I said, “Well, what am I going to do now? Am I really welcome or I’m not welcome?” And I said, “No, I’m going to show up. He said I would be welcome, I’m going to show up,” and I went out there. I was very nervous, very nervous. And you know what happened? All the guys on the team came running over to me and saying, “Wow, we’d never had a girl before, this is great.”

And one guy in particular was Arnie Briggs, a volunteer coach, he was the university mailman but he had an ex-marathoner and now he was injured and older, he is 50. He said, “We’ve never had a girl here before and I’ve been training with this team for 31 years. I’m now just a volunteer helping out with the team every afternoon and then I do a jogging if I can and then I go back to the post office.” And so, he saw me out running with the guys and, of course, I couldn’t keep up, I was really slow and he started jogging with me. And he got over his injuries slowly, slowly, slowly because I was slow on the grass and he would regale me every day with a story about his career as a marathon runner. He’d run the Boston Marathon 15 times and it was the day he was the hero in his own life. It was the day when he was more than just a postman, it was the day when people cheered for him, he would finish in the top 10, he was a pretty good runner. The girls at Wellesley would run out and kiss him and his name was in the newspaper.

And so, he inspired me so much to run long, we left the cross-country course and we went out and ran on the roads and we ran longer and longer and longer. And then one day I said I wanted to run the Boston Marathon too and he said, “Oh,” he said, “It’s too bad but a woman can’t do it.” And I said, “What do you mean she can’t do it?” and then I said, “I can do it,” and he said, “Oh, no, no. No woman could do 26 miles.” And I said, “Well, we’re running 10 miles now, Arnie,” and he said, “Ten miles is not 26.” But we argued and I told him a woman had run the Boston Marathon the year before without numbers, he didn’t believe it and he said, “I’ll tell you what, if you show me in practice that you can run Boston, I will take you and if you can do that distance.” And so, one day we did, we ran 26, I said that wasn’t far enough, let’s run another five, we ran 31 and he passed out at the end of the workout and that’s when he said, “You can go to Boston.”

True to his word, he helped me sign up, he insisted I officially enter the race. He said, “You’re a card- carrying member of the Athletic Federation, you’ve got to sign up for the race,” and so I signed up. Being a journalism student, I wanted to be a sports writer so I’d be signing my name, K.V. Switzer so I put down … I wanted to be J.D. Salinger too. So, I put down K.V. Switzer on the entry form, not to defraud them because that’s how I’d been signing my name, also my dad had misspelled my name on my birth certificate and everybody always misspelled Kathrine so I just decided to be K.V. Switzer. Anyway, the entry was accepted. I didn’t know that it was going to be an issue, there was nothing about gender on the entry form or in the rule book. So, now I’ve laid the story open to people, okay? The background is extremely important.

John Boccacino:

Absolutely.

Kathrine Switzer:

Yeah. So, showed up at Boston ready to run, it was pouring cold, freezing rain and snow. It was a real Syracuse day but it was the worst day in the history of the Boston Marathon in terms of weather before and up to 2018 when they had a hurricane, the absolute worst day, miserable conditions and everybody was really getting hypothermia and everything else. But at any rate, I started the race, again, the men were welcoming to me and, about a mile and a half into the race, the press truck went by, went crazy seeing a girl in the race and I was so proud of myself and Arnie was proud of me and my boyfriend had come along from the track team and he was a hammer thrower but, if a girl could run, he could run. And then came the official’s truck and on the official’s truck was the race directors and the race director completely lost his temper. He jumped off the bus and ran after me and attacked me in the race and tried to rip off my bib numbers and started screaming at me, “Get the hell out of my race and give me thosenumbers,” and calling me other names, “Get out of my race. Na, na, na, na, na, na, na, na, na, na.” And Arnie was trying to bat him away and it was really … And this was right in front of the press truck, okay? And I was in tears, I was trying to get away from him and he was pulling me by the sweatshirt when my hammer-throwing boyfriend threw a crossbody block into him and sent him out of the race, boom, on the side of the road. And then Coach Arnie said, “Run like hell,” and down the street we went. Now, you know what, John, you’re laughing-

John Boccacino:

Well, I-

Kathrine Switzer:

Okay. No, no. See, it’s a hilarious story.

John Boccacino:

Because of the adversity but also you had such a great team around you. And I’m laughing because it’s such an antiquated notion to think that a woman can’t … Back then, give our audience a little perspective too because the reason women didn’t run marathons, there were a whole bunch of preconceived notions that were out there.

Kathrine Switzer:

Right, but this official had bought into all of that but also he felt he was defending the rules in the race. But I said, “There are no rules and there was nothing about gender on the entry form.”

John Boccacino:

You paid your $3.

Kathrine Switzer:

I did.

John Boccacino:

You were eligible to run in that race.

Kathrine Switzer:

Right, right. I think it’s, what, 350 now or whatever but, at any rate, it was a very ugly situation and I was so upset. I thought I had really screwed up this important race, that some how I had stepped in the middle of something that was really sacred and made it bad and the press were all over me, “When are you going to quit? When are you going to quit? What are you trying to prove?” And I turned to one of them and said, “I’m not trying to prove anything, I’m just here to run,” and I’m going … God, I was only 20 years old and they were so harassing that I just looked down and then I said, “You might as well go to the front because I’m not dropping out of the race.” And finally, they left me and I turned to Arnie and I said, “I’m going to finish this race in my hands and my knees if I have to because everybody’s telling women they can’t do it and then they pull opportunities away from them so we can’t prove otherwise.” And in those days, try to imagine this, 1967, you weren’t even allowed to enter or apply to Harvard or any of the Ivy League schools and how are you going to get a law degree and compete with somebody who has a Harvard law degree? Then they say we were giving women opportunities but they can’t do it anyway. Well, of course you can’t do it if somebody’s going to try to rip your number off, right?

John Boccacino:

Yeah.

Kathrine Switzer:

Anyway, I went on, I finished the race, I forgave the official someplace around 21 miles when I didn’t have any emotions left, I realized he was a product of his time, that was his problem, and that I was going to have to make some changes in his attitude and other attitudes. Again, the guys in the race were wonderful, very supportive and then I was thinking, “Well, why aren’t other women here? What’s the problem?” And I was cynical about it, I said, “Women just not getting it,” and then I realized, hey, come on, you had parents who encouraged you, you had a cross-country team who encouraged, you had Arnie and that made all the difference. And suddenly I realized that if these women had the opportunity, just the opportunity, that’s all they needed. And by the time I finished the race, I said, “Okay, I’m going to be a better athlete, get my credibility together here, prove myself, play by their rules, whatever they are, and change those rules.”

John Boccacino:

The series of photos that the Boston Herald put out there, they’re iconic, they were part of Times 100 Most Memorable Photos. How much did the visual component of what you went through help to really with the groundswell of changing minds and changing perspectives on this?

Kathrine Switzer:

It was huge, John, it was everything. I think, two things. One, if I had walked off the course, this would be a ha-ha moment type of thing and the other thing were the photographs. And as a journalism student, I learned so much from this experience because I realized that the media made all the difference. And one of the media problems I had was that a lot of the reporters reported that I didn’t finish so they didn’t stick around to see that … It took me four hours and 20 minutes but they reported that I hadn’t finished and that was wrong. And if you’re going to be a good reporter, at the Newhouse School they taught us, get the facts, stick it out until you get the facts. And in fact, one of the reports came from the New York Times. So, what did I do? Knowing that the New York Times was the be-all end-all, everybody at Newhouse knew that the New York Times was it, I called them up, I said, “Hey, you made a mistake here, how about a little reprint, just correction? I just want you to know I finished the race, it’s important for people to know that.”

And the reporter on the other end who had reported it started taking notes and, Sunday edition, I was all over the front page of the Sunday edition with the most fabulous story and wonderful interview and that really helped change the tide as well because other journalist sources picked it up. But yeah, so it was a very good education for me that way but it was a long haul after that changing regulations. Again, here at Syracuse, I stayed here, took work after I graduated and worked on my master’s degree at night and, during that time, organized Syracuse Track Club which became the Syracuse Chargers and we began … I learned how to do race direction, I put on a race every Tuesday night, learned how to get sponsorship, learned how to get prizes, not prize money, but prizes and sponsorships, and then learned how to work the regulations. Sat out my little time with the Athletic Federation, came back, took a leadership role and decided I would make change from within which you need to do. So, that led to then creating the work to get to the Olympic Games which we can talk about.

John Boccacino:

A lot of people, when faced with their darkest moment, you have the two choices. Are you going to fight or are you going to fight? And you chose to fight and it’s so applaudable what you did because, eventually, your persistence led to the women’s marathon being admitted to the Summer Olympics in 1984 and the groundswell and popularity of running. What was your thought process? Why did you take that option and say I’m not going to let what happened to me happen to other people who want to follow in my footsteps?

Kathrine Switzer:

Because it was wrong. I was raised by parents who said you know right from wrong so go for what’s right. And I knew it was going to be very time-consuming and discouraging and a lot of cat calling, the hate mail I received was not nice but I received really good mail so I threw that hate mail away and kept a good mail. I wasn’t really trying to challenge them, I was just trying to correct the error that the establishment had made but, more than that, I wanted women to know how great you can feel when you’re running. As long as I ran, I felt empowered, I felt like I could overcome anything. And it is, running is naturally empowering, it’s a super, super endorphin high and so it’s very, very beneficial for thinking and clarity and I did a hell of a lot of thinking. When you’re training for a marathon, you’re out there for hours alone and you can take on a problem and solve it.

One of the things I solved is what is going to take to get the women’s marathon in the Olympic Games? So, every night I would think of another part of that problem and then finding a solution and the solution again and again came to opportunity. And what I did then, by the time I had gotten my master’s degree, I just said, “Okay, I’m going to go to the Munich Olympics, I’m going to work as a journalist, freelance journalist, and I’m going to try to figure out how to make this happen and I’m going to meet some political people there.” Well, the Munich Olympics were a real trial by fire, it was a horrible situation and I realized suddenly that this is very political at lots of different levels. When you are going to murder 11 Israeli athletes, there’s a lot going on here and that certainly takes precedence. So, we’re getting the women’s marathon in the Olympic Games but it is still a series of prejudices and discriminations, so I was more determined than ever and what I did is I said, “Okay, opportunity, create the opportunity. “So, I thought, hey, if I create a series of races around the world that are for women only in the streets, make every woman welcome and treat her like a hero, make it feminine, make it non-competitive, competitive at the front if you want to be but make every woman regardless of age or ability welcome. And so, what’s going to make that happen? Sponsorship. I’d learned that getting trophies for Syracuse and so I said, “Okay,” so I wrote up a business proposal. So, again, my journalism degree came in really handy, wrote a really gangbusters proposal and decided to shop it around. And I decided to take it to Avon Cosmetics first because everybody knew Avon, it’s a women’s company, it’s cosmetics, it’s safe for a woman, if you see what I mean. It’s okay, it’s a lipstick. And so, I took it to their executives thinking they’re never going to buy this thing but here it is. I got a called the next day from the guy I gave it to and he said, “You know, we’ll probably never do anything with running but, honestly, this proposal is just incredible. And if you can think like this, we would love you to work for us.” I said, “Nah, he’s just joshing me.”

And I said, “Oh, great. Well, thanks, I’m glad you liked it.” He said, “So,” he said, “Would you be interested in working for us?” “No.” He said, “What would it take to have you here to work for us?” And so, I knew he was joshing me so I was making all of $13,000 a year that year, it was big pay, I said, “30,” and he said, “That wouldn’t be a problem.” And that’s when I learned you should ask for what you’re worth. I had no idea that I could earn $30,000 and I thought, “Oh, my God, am I up to the job?” Suddenly

self-doubt and I said, “You’re up to the job.” I went in there, we launched that thing, short story now. Eventually, we had races in 27 countries for over a million women, 400 races, it was a huge global program. And I took it to places like Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand, Japan, they’d never even had women’s sports much less open road race, the women came by the thousands.

John Boccacino:

Ooh.

Kathrine Switzer:

Yeah. And so, now I had the data and statistics to present to the International Olympic Committee. We had the participation, we had the sponsorship, we were on media all over the place and we had performances, and we had the international representation that they essentially had to vote when those federations voted, and they voted in the women’s marathon in 1981 for the ’84 games by a vote to nine to one. So, there we go.

John Boccacino:

And I love the fact that … And I mentioned earlier, you talked about opportunities for women, giving them the equal ground. Running for you, I see the smile light up and your eyes light up when you talk about running on the race. What is it about running for you that has been just so rewarding and so fulfilling?

Kathrine Switzer:

It’s given me everything. Everybody, they ask the question what is the number one thing, I’ll just say, listen, running has given me just about everything. It’s given me my religion, it’s given me my husband, it’s given me my travel, my job, my perspective but the biggest thing I think it has given me, my health, my wellness and all that kind of stuff, but the biggest single thing is it’s given me me. It’s given a perspective on myself and given me empowerment and belief in myself and that’s what everybody in theis lacking at some time where they are and say, “Oh, my God, can I do that?” and I just go out for a long run and take a deep breath, yeah, you can do this. So, it is quite miraculous and it’s easy and it’s cheap.

John Boccacino:

And anybody can do it anywhere.

Kathrine Switzer:

Anybody can do it anywhere.

John Boccacino:

Well, I love too the fact the humble origins of … Because, really, you could say that your running career did start here at Syracuse when you were working with the cross-country team and Arnie and everything and I want to bring this back to the Syracuse connection for a second. What drew you to Syracuse to study journalism, to study English and then go on and get the public relations master’s degree?

Kathrine Switzer:

Well, what drove me to come to Syracuse was the following. First of all, in high school, I was the first graduating class so we were the first all the way through for four years. And when I first went into this high school, I wanted to work on a high school newspaper and I wanted to write sports because the women weren’t getting any coverage, the girls were not getting any coverage and we actually had a field hockey team and a softball team. So, I got some pump by writing my sports stories and I loved the journalism and I loved the writing so, throughout high school, I carried on with the journalism. And then, when I went to college, my parents lived in Virginia and they really wanted me to go to a state sponsored school. So, there was only one co-ed school in the whole of Virginia at the time which was Lynchburg College, which is now Lynchburg University, and I went there for two years and one of my creative writing teachers was a Syracuse grad, her name was Wilma Washburn and she had a journalism degree.

And so, I took her journalism courses, we would talk about Syracuse, she would talk about her Syracuse days. I took a creative writing course and did well in that as well and I realized it was writing that I really loved and so I’d said, “Look, to earn a living as a writer, as a journalist, as a girl, especially one who wants to write sports, you better have the best damn passport in the world.” And I looked and I said there’s Columbia, there’s Missouri, there’s Syracuse. Syracuse accepted, Syracuse I went to and I never looked back. I had that passport and that was really, really essential and I thought I had a pretty good education. Fueled by the work I was doing, organizing, running events and learning how to do the marketing, I said, “Really, my passion is also journalism, public relations, marketing, that combination of making an event happen and making change and combining all those things,” so I went back to … Actually, my masters is in public relations.

John Boccacino:

Running gave you who you are, Syracuse gave you the skills to fine tune yourself and find what you want to do with your career. Is there a tangible lesson that you learned here at Syracuse that is with you every day everywhere you go that sticks with you?

Kathrine Switzer:

Yeah, the weather. I’ve got to tell you, it was the worst conditions I think ever in the history of Syracuse is the year I was there. We had nine meters of snow that year. We didn’t see bare ground from October until May and I trained through that for the Boston Marathon and it was tough. There were nights that it was 30 degrees below zero, I’m not kidding you, and we were out there just in a sweatsuit. Arnie and I running in that stuff, in pitch black and the blizzards and stuff like that and I realized I was really tough. So, when I got on the starting line of the Boston Marathon ’67, everybody else is getting hypothermia, hey, this is a spring day for us. But I say it metaphorically meaning that, when all the conditions around you are bad and you can thrive and learn from them, there’s no opportunity, really, that’s a bad one and that’s what I learned. And I’m sorry, the university, of course, yeah.

John Boccacino:

Sure, of course, and the fact that you’ve come back and I know … We’ll talk about speaking to students and the advice but I want to ask you one question. I get the sense, when you start something, you finish it and that was exemplified by the Boston Marathon, you were not going to let the race official prevent you from finishing, you weren’t going to let the adversity stop you. Where did you learn that lesson of you need to finish what you start and you need to be prepared for what you’re going into?

Kathrine Switzer:

From my father, absolutely, absolutely. He said, “Honey, when you start something, you better finish it,” and his voice was echoing in my ears when the press was saying, “When are you going to drop out? When are you going to drop out?” And I felt like I really did want to go drop out, I just wanted to go hide, I felt so ashamed and embarrassed, and they were humiliating me and my father said, “You start something, honey, you finish it,” and so definitely did so that was really, really important to me. Another thing is it was my dad who started me running because I wanted to be a high school cheerleader, whoo. My dad said, “Oh, honey, you don’t want to do that, life is to participate, not to spectate and you shouldn’t cheer for other people, people should cheer for you.” And I said, “Well, Dad,” and he said, “Your school has something new, it’s called a field hockey team and, if you ran a mile a day, you’d be the best player on the team.” He was a very motivating guy.

And I said, “I can’t run a mile,” and he said, “Sure you can, you can go right now and you can run a mile.” And I said, “I can’t,” and he said, “Come on, I’ll show you.” We went outside, measured the yard, seven laps, he said, “Okay, just do it, just try it,” and I took off and he said, “No, no, no, go slow. It’s not about fast, it’s about finishing the job.” I remember all these things. And so, when I finished, I said, “Dad, I did it, I did a mile,” and he said, “Yeah, now you do it every day.”

John Boccacino:

That lesson clearly stuck with you though too.

Kathrine Switzer:

They do, they do, yeah.

John Boccacino:

And I love hearing the beginnings of where people come from and what shaped their careers that they take on and I love what you’ve done with 261 Fearless, the fact that you’ve got more than 5,000 women, girls of all ages, of all backgrounds, all abilities coming together. You mentioned this earlier but what do you think is the biggest impact that 261 Fearless has had in the ways of empowering and lifting up other women through running?

Kathrine Switzer:

John, it’s an early question because we’re really only 10 years old and we’re in 13 countries already. This is a non-profit and non-profits, foundations, et cetera, really only reach their fullness after a couple of decades so we are on the right track which is terrific. So, the influence we’ve already have is we have proved that, regardless of your age, your ability or your background or whatever, if you could get out and put one foot in front of the other, you’re going to become empowered. If you want to lift a woman up, just show her how to run but she needs a friend. And women, we look at all the modern women out running, there are thousands and thousands of them but there are so many women who are isolated or restricted by religious convention or social convention or cultural mores or the old myths that I grew up with which is, if you run, your uterus is going to fall out so you’re terrified. Do I really want to run or get big legs and turn into a man? Those are all the things they told us and those myths still exist. And so, you say, okay, well, how are you going to reach these women? Well, you need to do it at the grassroots level and you need to take them by the hand and say, “Hey, look, this isn’t about being competitive, it’s just about come out and have a jog or a walk with us and go get coffee or something afterwards.” And yet, these women who are taking you by the hand, they are trained coaches so we have them as, really, people who know how to do that and reach out to them. And we are going to work and we are working village by village, city by city, country by country and just going in at the grassroots level and the word spreads. My dream, after getting the women’s marathon in the Olympic Games, I remember I was doing the TV broadcast by that time, another Newhouse score. I came out of the stadium and said, “Okay, we did that. We got the women’s marathon in the Olympic Games,” at 90,000 people screaming and 2.2 billion viewers, unbelievable, that’ll change the world I said.

It was only about a week later you hit that postpartum funk and I thought, “Oh, that’s really great for women who can train and go to a race. How about those women who they’re under a burka in Afghanistan or North Africa or they’re isolated in their home with domestic abuse? How are we going to reach those women?” And suddenly, that old bib number, 261, became a number meaning fearless in the face of adversity and it absolutely went viral. People were telling me it’s changing my life, I’m taking courage from you and what it really means is that they need a symbol to make something happen and that’s what inspired us to create the non-profit 261 Fearless. Not a business, a non-profit.

John Boccacino:

Absolutely. And 261 Fearless is … And the fact that the bib number … Is it even possible to comprehend you didn’t enter the Boston Marathon looking to make history but, out of that troubling moment, just how much good has come from that?

Kathrine Switzer:

I know but from the worst things can come the best things and that’s what I’m going to be telling the class today. I said, “If something is wrong, there’s an opportunity to change it, that we can then reverse it. You look at what’s the solution to this? Let’s do the solution.”

John Boccacino:

Well, the last question I have for you, Kathrine, and I’m so grateful for you making the time, you’ve had such a lovely story to share with our audience here. You’re talking to students coming up here for fall classes, you obviously love running and you love Syracuse. If somebody asked you to define what does it mean to be an alumna of Syracuse University, what would you say?

Kathrine Switzer:

I would say that it is a very powerful thing and that it is … I was going to say a sisterhood and a brotherhood. It is a very important friendship and network and a sense of unity, of purpose. And certainly, I think, in Falk, which is a new school relatively and it’s Syracuse but growing wildly and powerfully into something that is educating students for a universal language. Sports is a universal language, sports doesn’t need Spanish, English, whatever. You’re watching a soccer game, you know what’s going on here. And running is a universal language and so, through this universal language, I think getting an education that enhances that understanding globally is going to only increase the luster of Syracuse University.

John Boccacino:

I’d be remiss, I have one more question that I think you’ll appreciate me asking you before we wrap up here. Tell our audience about the work you’re hoping to achieve with the university, our library and our archives.

Kathrine Switzer:

Oh, boy, I had a wonderful meeting this morning with them and I have … I guess I’m a hoarder at a certain point but I couldn’t bear to give up any of the videos or film or writing or the brochures and all the work we had done leading to get the women’s marathon in particular into the Olympic Games and I kept it all. And my husband, very, very gratefully to me, went down to my basement and at least put them in boxes by year. But there is a ton of material and it’s now very valuable and I’m hoping that the acquisition and my gift of all of that material to Syracuse University Library will result in probably the biggest collection and best collection of women’s running history, marathon history anyway, distance running in the world. And it is a joy to think that it will be public accessible which I think is everybody’s ambition.

John Boccacino:

It’s really a treasure trove of memories to go down and share it with the future generations because we need to keep telling these stories of overcoming adversity and, again, I can’t thank you enough. Kathrine Switzer has been our guest here on the ‘Cuse Conversations Podcast, a revolutionary trailblazing pioneer who is humble as can be too. We’ve really enjoyed your stories, thank you so much, Kathrine.

Kathrine Switzer:

Thank you, John, great to be here. Go Orange.

John Boccacino:

Thanks for checking out the latest installment of the ‘Cuse Conversations Podcast. My name is John Boccacino signing off for the ‘Cuse Conversations Podcast.

A Syracuse University News Story by John Boccacino was originally published on December 9, 2024