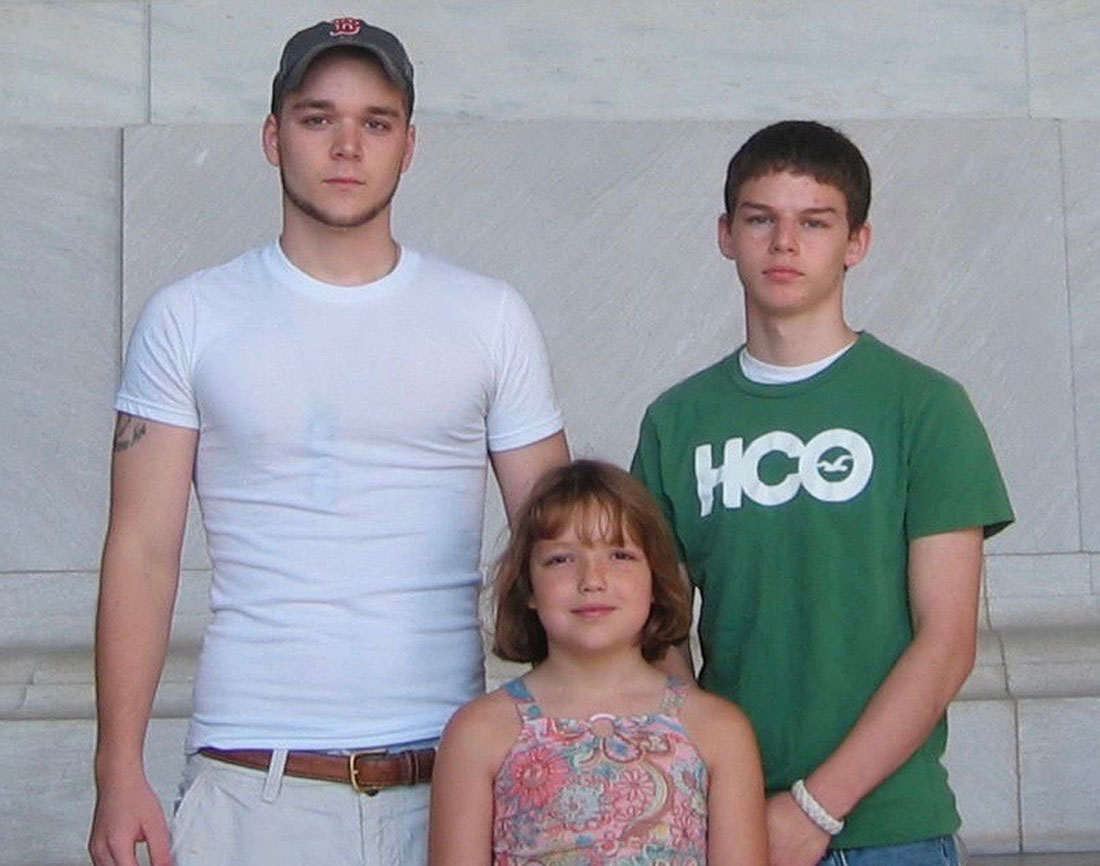

Kiersten Edwards was 8 years old when her older brother, Daniel McPeck, left home to join the U.S. Marine Corps. And as Edwards grew older, she spent a lot of time away from home competing for the U.S. Snowboard Team.

But even as they were separated by 13 years and thousands of miles, they remained close and McPeck always had a special greeting for his sister.

“She knew every time she spoke to her brother, he would say, ‘How’s my beautiful little sister?’” says James Edwards, Kiersten’s father.

But on Christmas day in 2017, when Edwards was a senior in high school, those sweet messages were silenced forever when McPeck died from a fentanyl overdose.

Edwards’ journey since her brother’s death has not been a straight line. She considered becoming a doctor, enrolled at Syracuse University for engineering, and is now a public health major who’ll graduate in May. During her time at Syracuse, Edwards discovered that her desire to make the world a better place could be realized through public health initiatives such as addiction prevention.

“I’m never going to be able to bring my brother back, but maybe I can positively affect the lives of other people,” Edwards says. “I think that’s what drives me, taking the trauma and pain that I experienced and really trying to protect other people from it.”

As a community volunteer, an award-winning teaching assistant in the Department of Physics, and the recipient of multiple Syracuse University Office of Undergraduate Research and Creative Engagement (SOURCE) awards for her public health research, Edwards has already made a significant difference in the lives of others. A double major in public health and neuroscience with a public health concentration in addiction prevention, Edwards is also designated as a 2023 Falk Scholar, the highest academic award conferred by the Falk College of Sport and Human Dynamics.

And to cap off her exceptional four years at Syracuse, Edwards has been named a 2023 Syracuse University Scholar–the highest academic accolade given to graduating seniors–and she and her fellow scholars will lead the student processional at Commencement.

It seems Daniel McPeck’s beautiful little sister is doing just fine.

“I’m extremely proud of what she’s doing, and Daniel would just love it,” James Edwards says. “Daniel loved his family and let them know it every time he saw them. To have her find some good in it and honor him that way, nothing can make me happier.”

‘Exercise Her Mind’

Edwards’ fascination with health started with her own. When she was around 4, she and her father were four-wheeling on the trails in the woods near their Vermont home when a tree branch fell and punctured her leg.

Her parents rushed her to the doctor’s office, where she squirmed on the table until the doctor asked if she wanted to sit and watch him stitch her up. “Yeah, I want to watch,” Edwards recalls saying, “this is super cool.”

“I was like, uh, I think I need a chair,” James Edwards says, laughing. “I’m all woozy, and she was glued to it.”

Edwards’ tolerance for pain would be tested as she developed into an Olympic-level snowboarder who competed for World Cup teams in multiple junior world championship events. Her injuries mounted, and she needed surgery for a torn anterior cruciate ligament in her knee.

The doctor who performed her surgery was a family friend who was also a doctor for the U.S. Olympic team. Sensing her interest in medicine, he asked if Edwards wanted to shadow him for a day. Following a day of watching knee and hip replacement surgeries, Edwards decided she wanted to be a surgeon.

Edwards rehabbed her knee and eventually returned to top-level competition, but her heart was no longer in it.

“Snowboarding was fun and a passion, but it wasn’t what she was meant to be,” James Edwards says. “I think she was tired of training and exercising her body and wanted to train and exercise her mind.”

‘I’m Learning from You’

Edwards had her future mapped out: Study biomedical engineering, attend medical school, and become an orthopedic surgeon. Syracuse University had always been on her radar because her sister, Alicia, graduated from Syracuse in 2006 and Edwards’ “first crush” was basketball star Carmelo Anthony, who led the Orange to the national championship in 2003 when Edwards was 3.

“I sobbed when he left Syracuse because it didn’t quite make sense to me why he was leaving,” Edwards says, referring to Anthony’s departure from Syracuse in 2003 for the NBA.

Like Anthony, Edwards eventually had to make a pivotal decision about her future. In her freshman year at Syracuse, she met her current partner, Andrew Nibbi, and started to question if spending the next eight years becoming a doctor would be the best thing for her personal life. While she was still interested in health, she started to think about other career options and considered transferring to another college.

In the spring of 2020, her freshman year, Edwards took an introduction to physics class taught by Walter Freeman, an associate teaching professor in the Department of Physics in the College of Arts and Sciences. That was at start of the COVID-19 pandemic, and as students transitioned to online learning Freeman created a group chat for the class of more than 400 students. Edwards and Nibbi were among the students who would stay connected with Freeman late into the night to discuss their “thoughts and feelings and hopes and dreams and fears” during that frightening time, Freeman says.

In the fall, Edwards and Nibbi joined Freeman’s introduction to astronomy class. For their final project, Edwards wrote a poem that compared gravity to the social cohesiveness forces that were being strained during the pandemic. Nibbi wrote stirring music to accompany Edwards’ impassioned reading.

Freeman was floored.

“I returned their project ungraded,” Freeman says. “In these cases, I usually give students extra credit, but I told them I’m not qualified to give you a grade on what you have done here because I’m learning from you and not the other way around.”

As Edwards gravitated toward public health and Nibbi toward the Newhouse School of Public Communications to pursue a career in filmmaking, Freeman became their sounding board. Freeman recognized Edwards’ many talents, and he asked her to join his group chat in the spring of 2021 to help students with homework. In the fall, she was hired as a teaching assistant for the astronomy and physics classes that she had taken with Freeman.

In the spring of 2022, Edwards was recognized for her ability to connect with students with an Undergraduate Teaching Award from the Department of Physics.

“She has been a cultural leader among other teaching assistants in that she understands what we are about, the supportive environment we’re trying to create, and the human values of our course,” Freeman says. “She has always done what needs to be done to take care of people.”

‘Why Are You All So Happy?’

In August 2020, as Syracuse University was about to enter its first full school year of the COVID-19 pandemic, Edwards was hired to work in the testing lab that was set up in the Life Sciences Complex. There, she met Falk College Associate Professor of Public Health Brittany Kmush and students majoring in public health.

“I was like, what is this public health thing and why are you all so happy?” Edwards says, smiling. “This was before we had a vaccine and everything was shut down, and what struck me was that everyone in that lab who was a public health major seemed just a lot happier than a lot of people I knew.”

Whether they were in the lab for pay, an internship, or as a service-learning course for public health, the students were “generally happy and they enjoyed contributing to something that directly affected their lives,” Kmush says.

“We were making the (COVID testing) pools, so once they got the hang of it, it was pretty monotonous and they could talk and chat with each other across the tables and get to know each other and talk about their different degrees,” Kmush says.

Intrigued, Edwards started investigating the major and emailed Undergraduate Director and Associate Professor of Public Health Maureen Thompson to ask questions about the different paths she could take with public health, including addiction prevention.

Through her conversations with Thompson and her advisor Professor Dessa Bergen-Cico, and in her classes with public health professors like Kmush, Associate Professor Ignatius Ijere, and Assistant Professor Miriam Mutambudzi, Edwards came to identify the social determinants of health (food insecurity, racism, education, etc.) and their devastating impact.

“There’s one particular class that I took with Dr. Mutambudzi that really emphasizes how cultural disparities affect health throughout somebody’s lifetime,” Edwards says. “There are statistics and stories that have really affected me that came from this class and all of my other classes (at Falk) that emphasize to me the importance of looking at racial and gender disparities in health, why are they there, and what can we do to fix them?”

After taking Kmush’s epidemiology course, Edwards asked if she could get involved in research and Kmush suggested SOURCE. With Kmush as her faculty mentor, Edwards received a grant to pursue her idea of studying Syracuse University’s COVID data and comparing it to the University’s COVID policies to see if she could identify trends that contributed to more or fewer cases.

What makes Edwards’ research unique is that she’s using data from the semesters when it was mandatory for all students to test. That gives her a more complete picture of a specific population than, for example, a county’s data that will always be incomplete because not every resident reported the result of their home test.

Edwards hopes to complete her analysis by graduation, and she’ll partner with another student who’ll work on getting the research published next year. Kmush says the findings can eventually be used to make informed decisions about vaccines, masking, and other protocols for COVID, RSV, the flu or whatever else comes along.

“I want to feel like I’m making a difference, so that means I want the research I do to support policy changes for the positive,” Edwards says. “Making a change in policy is the way you affect real human lives.”

‘Go Out and Get It’

Following graduation Edwards will return home to Los Angeles, where she’ll join Nibbi, who’s working as a digital imaging technician in the film industry. Eventually, she wants to pursue a Ph.D. in behavioral neuroscience with an emphasis on how to diagnose and treat addiction and substance abuse disorders.

But for now, she’s taking a gap year to work as a research assistant at Samuel Merritt University, a private university focused on health sciences that has campuses in Los Angeles and Oakland. Her research, which has already started, will focus on burnout and how it affects the workforce with an emphasis on nurses, women, and underrepresented populations.

“I want to figure out a way to use the research I’m going to be doing on the neuroscience side of things in public health and then, moving forward, how can we practically apply this to the lives of humans?” Edwards says.

Those close to Edwards have no doubt she is going to make a difference and save lives.

“She really embodies the virtue of the well-rounded academic, of being a scholar of not just this thing or that thing, but many things, and putting all of those talents to use to try to make the world more than what it should be,” says her mentor, Freeman.

“Her future is all laid out for her,” says her father, James Edwards, “and she’s going to go out and get it.”

For her public health internship this spring, Edwards is working in Syracuse for the needle exchange program at ACR Health, a not-for-profit that provides a variety of support services. For Valentine’s Day, the clients–those with drug issues who are exchanging needles at ACR–were invited to write anonymous notes to the staff.

One note will remain forever etched in Edwards’ memory and it could have easily come from her brother Daniel during his most difficult struggles. It read, “Thank you for still realizing we’re people.”

“I think there are a lot of people who are forgotten,” Edwards says. “So much of what I want to do is trying to highlight and remember those people.”