Food Studies News

Can Kelp Help?

While the majority of climate change research focuses on reducing and capturing carbon dioxide, less attention has been paid to methane emissions, despite the gas having 30 times the warming effect. Over a quarter of the United States’ total methane emissions are derived from enteric fermentation (cow burps) alone. Emerging research finds that feeding certain species of algae (seaweed, kelp or microalgae) to cattle can reduce their methane emissions by 80 to 99%. Unfortunately, most farmers and bovine nutritionists are unfamiliar with algae-based feed supplements, and the supplements are not always available and can be expensive.

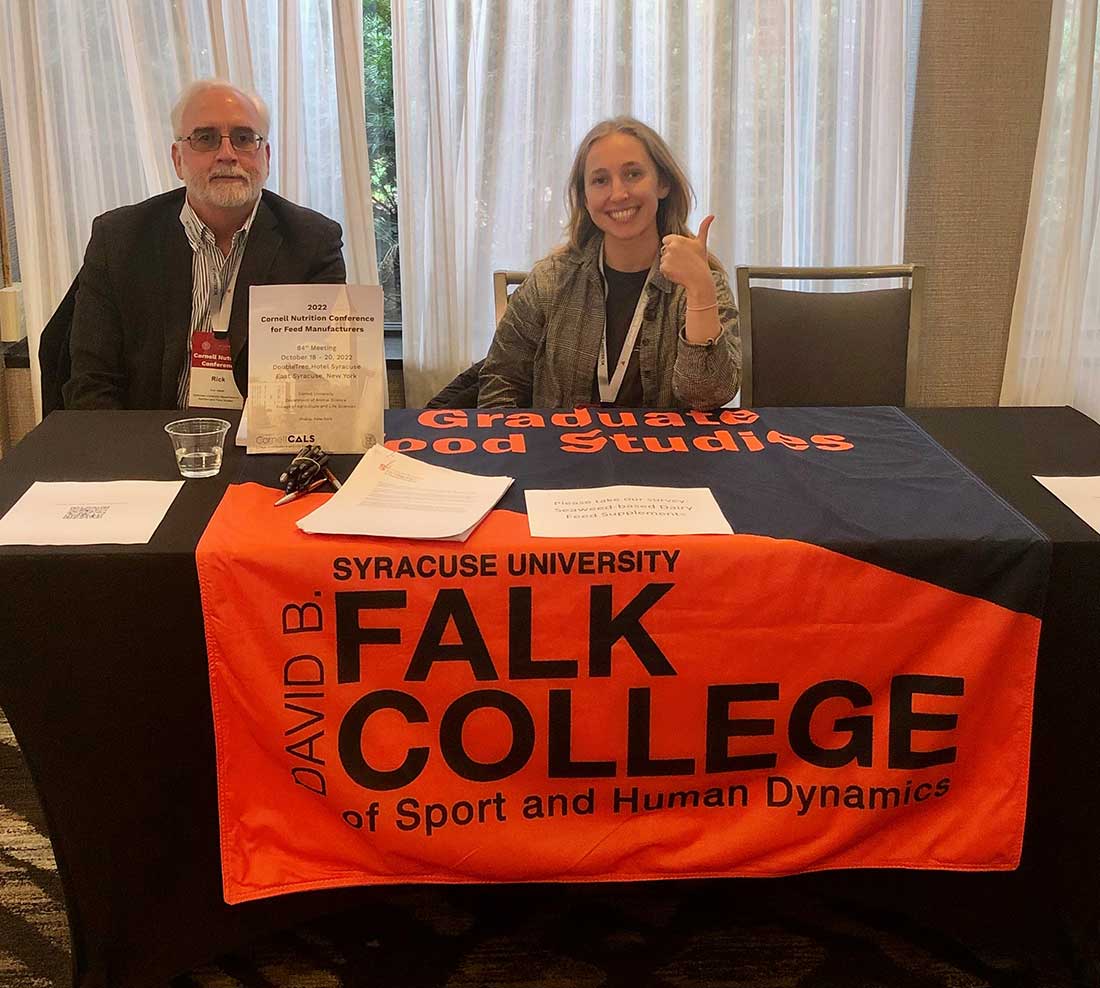

A faculty member and graduate student in the Falk College of Sport and Human Dynamics are among a multidisciplinary team of over 50 researchers tackling this issue. Falk Family Endowed Professor of Food Studies Rick Welsh and graduate research assistant Michelle Tynan are part of the $10 million Coast-Cow-Consumer project, funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture’s (NIFA) Sustainable Agriculture Systems Program.

Welsh and Tynan have been surveying and interviewing conventional (non-organic) and organic dairy farmers, as well as dairy nutritionists, about their knowledge of algae-based feed supplements, the level of interest farmers and nutritionists have in feeding the supplements, and the barriers faced in implementation.

“Without dairy farmer and professional dairy nutritionists’ understanding and comfort with the technology, any potential benefits cannot be realized. Therefore, listening to and learning from farmers and other dairy professionals is key,” Welsh says.

Familiarity Key

Over the summer, Welsh and Marie-Claire Bryant ’22, who received an M.S. in food studies, held focus group sessions with organic and conventional farmers. They found that organic dairy farmers were more familiar with using algae-based feed supplements than conventional farmers, since many organic farmers already use it as a health care aid instead of conventional products, such as antibiotics. In focus group sessions, organic farmers explained their experience that feeding algae has improved cow fertility, reduced pink eye infections and lowered the incidence of mastitis of the udders.

Those sessions also revealed that conventional farmers were skeptical of the health claims, but could be interested as more science emerges and if using algae-based feed supplements is cost-effective.

Their reports also made it clear that farmers would adopt algae supplements to promote cow health—but not to reduce methane—unless a methane-reduction program was incentivized by the government, dairy cooperatives or milk manufacturing firms.

Nutritionist Survey

More recently, Welsh, Tynan and food studies graduate student Ryan Fitzgerald conducted a survey of dairy nutritionists at the Cornell Nutrition Conference. They found that most nutritionists do not recommend algae to their clients, not because they don’t believe it is effective, but because they don’t feel they know enough about it. The nutritionists wanted to see more peer-reviewed research showing the efficacy and safety of algae-based feed supplements.

Welsh and Tynan plan to continue surveying dairy farmers and nutritionists and will be working with other project members to understand the value of those supplements for improving farm income and herd health, as well as protecting the environment.

A Bonus Economy?

Popularizing algae-based feed supplements could also help another type of farmer—the lobster fishers of Maine, according to Welsh. Given algae’s ability to grow well in cooler Maine waters and its harvest period opposite the lobster season, it could provide an alternate source of income for that region. Algae (seaweed) is known for being able to sequester large amounts of carbon from the atmosphere, Welsh says.

Research on methane gas reduction is particularly pertinent now. President Biden recently announced new initiatives to address what his administration describes as “super-polluting methane emissions—a major contributor to climate change,” including emissions from beef and dairy systems. New York Gov. Kathy Hochul, in concert with the state’s Climate Action Council, also just announced goals to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 40% by 2030 and 85% by 2050.

The Coast-Cow-Consumer project is now entering its second of five years. The project team includes researchers from Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences, Clarkson University, Colby College, Cornell Cooperative Extension, Kansas State University, University of New Hampshire, University of Vermont, William H. Miner Agricultural Research Institute and Wolfe’s Neck Center for Agriculture and the Environment.

“The opportunities for collaboration are as deep and wide as the ocean itself,” says researcher and graduate student Tynan. “We are hoping this research contributes to a sea change in methane reduction, sustainability and cow health.”

Memories We’ll Always Treasure

Each year, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics holds the Food & Nutrition Conference & Expo (FNCE). The Academy comprises the largest group of food and nutrition professionals in the world, and each year members from around the country travel to experience everything FNCE has to offer.

Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic put a halt to FNCE. But after being held virtually for the past two years, the Academy and nutrition community was excited to welcome FNCE back in person this October in Orlando, Florida.

This year’s cohort of dietetic interns from Syracuse University were encouraged and supported by Falk College to attend FNCE. All 10 interns, along with multiple Falk nutrition faculty, traveled to Orlando for a weekend of networking, professional development, and fun!

FNCE 2022 did not disappoint and offered countless educational sessions, an impressive expo floor, and exciting networking opportunities. Each intern expressed immense gratitude for the opportunity to attend this inspiring event. As future dietitians, this was a valuable experience that inspired us as young professionals and reminded us of the important field we are working to enter.

When asked by our director to reflect on my experience, I noted that, “Connecting with other students and dietitians and hearing about their experiences and passions is inspiring and confirms that I am on the right track in becoming a dietitian.”

The conference was held from Oct. 8-11. After an exciting opening ceremony and hearing from Academy President and Syracuse University alumna Ellen Shanley, the conference began. There were sessions throughout each day, varying from topics such as sustainability to inflammation and malnutrition to cultural differences and accessibility.

There was truly no shortage of opportunities to learn. When the interns were not attending sessions or checking out research posters, we visited the expo floor. This year, more than 200 organizations attended FNCE. Brands and companies big and small showcased their products and services and to no one’s surprise, it was delicious!

Orlando showed its Orange spirit that weekend with representation from Falk College! Assistant Professor Jessica Garay presented research posters with student contributions titled “The Effect of a 3-month Lacto-ovo Vegetarian Diet Intervention on Diet Quality” and “The Effect of a 3-month Lacto-ovo Vegetarian Diet on Inflammation.”

Associate Professor and Undergraduate Director of Nutrition Kay Stearns Bruening presented a future practice poster titled “Focused interdisciplinary learning experiences improves awareness of interprofessional health profession skills.”

One of the most exciting events of the weekend was when the Syracuse University Dietetic Internship accepted the School Spirit Award. The interns and director Nikki Beckwith attended a reception with Academy President Shanley and heard words of professional advice from multiple academy board members. Nikki and interns were honored to accept the award from alumna Shanley and show their Orange pride!

The Syracuse community was so proud that one of our interns, Rebecca Garofano, presented this year. Rebecca and her research partner, Helen Midney, presented on their research titled “Food Solidarity: Lessons from a Farmworker Community’s Food Pantry Garden.” (In April, Garofano was honored with the Outstanding Dietetics Student Award by the New York State Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics.)

All nutrition students hear about FNCE and the amazing opportunity it provides, however after experiencing it firsthand, the Syracuse University dietetic interns agree that this is an understatement. Having the opportunity to travel as a program was a memorable experience. We left with knowledge and insight on diverse topics, connections to professionals in the fields, and memories we will always treasure.

Editor’s Note: Baker was joined in Orlando by nine other dietetic interns who are graduate students and will complete their internships in May: Asma Bukhari, Dahabo Farah, Rebecca Garofano, Natalie Krisa, Olivia Mancabelli, Maureen Philzone, Jennifer Pope, Sydney Teeter and Shenna Tyer. If you’re interested in a career in nutrition and dietetics, learn about the programs offered through Falk College on the Department of Nutrition Science and Dietetics webpage.

—Maddy Baker ‘23, Dietetic Intern, Department of Nutrition and Food Studies

Growing Food Activism

“Moving across the country in pursuit of my master’s degree in food studies was a very risky but meaningful decision. I wanted to get more involved in the local workers’ movement, as much of my academic interests and personal background align with labor rights of agricultural migrant workers,” says April Lopez G’23.

The Mark and Pearle Clements Internship Award allowed her to pursue a summer internship combining her passions of food and activism. “Bridging that connection led to an internship where I was responsible for assisting different efforts focused on improving working conditions for immigrant low-wage workers in the state of New York, who were severely and negatively impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic,” Lopez says. “This would not have been possible without the Clements Award. The funding made it possible for me to stay in Syracuse for the summer, lobbying for a permanent unemployment fund for excluded workers, health care for all and legal services for immigrant workers.”

Mark and Pearle Clements Internship Award is open for juniors, seniors and graduate students of any major seeking to further their career development through undertaking self-obtained unique internship opportunities. The award provides students with financial assistance to help in the pursuit of their unique professional goals.

Awards may range from $1,500 to $6,000, crucial for students who may not have the money needed to pay for internship-related travel, accommodations, required materials or living expenses. Erin Smith ’15, Syracuse University Career Services internship program coordinator, knows how pivotal this award is for ambitious students.

“The Mark and Pearle Clements Award is a special honor for Syracuse University students who go above and beyond by proactively planning for and creating unique summer experiences,” says Smith. “It is a privilege to oversee the application process for such an impactful award.”

Winning students are able to use the award to pursue unique internships that directly related to their professional interests. In doing so, they received extraordinary hands-on opportunities that would not have been possible otherwise. Among all awardees, gratitude is expressed not only for the support of the award but also for the experiences and industry connections gained along the way.

Down to Earth

On a cool but sunny early October morning on Syracuse University’s South Campus, eight graduate students from the Food Studies program at Falk College sit in a circle at Pete’s Giving Garden and talk dirt.

No, not gossip about their professor, Estelí Jiménez-Soto. Actually, she’s right there with them, sharing her thoughts occasionally but mostly listening as student Michelle Tynan leads a discussion about their understanding of soil, why soil composition matters, and even if they’ve considered the type of soil that surrounds their homes or apartments.

Eventually, the students split into two groups and collected soil samples from the garden, the lawn, and the bordering forest. Literally getting their hands dirty, the students compared the properties of soils and applied what they had learned about agroecological practices to what they observed and measured that day.

Welcome to the graduate-level agroecology course, where students “discuss soil, food sovereignty and regenerative agriculture, and learn how agricultural systems can be designed in a way that meets ecological and social sustainability goals,” says Jiménez-Soto, an assistant professor in the Department of Nutrition and Food Studies at Falk.

And what did the students find in the soil in and around Pete’s Giving Garden?

“We found many more microarthropods (small invertebrates that act as decomposers) in the forest soil than we did in any other sample,” Tynan says. “The forest soil was much darker, indicating a higher level of organic matter. Agroecological theory teaches us to learn from natural processes–like how soil is generated and how nutrients are cycled in a forest–and apply this to agricultural systems like a farm or garden.”

For the agroecology students, Pete’s Giving Garden provides an ideal space to test the concepts they learn in class. The garden is also the epicenter of a series of collaborations across the Syracuse University campus that involve Falk and the Food Studies program.

For example, two of the agroecology students–Gabriel Smith and April Lopez–work on issues involving food insecurity on campus as the garden has provided more than 600 pounds of produce for the Hendricks Chapel food pantries. Smith is the manager at Pete’s Giving Garden, and he and Food Studies graduate student Ethan Tyo appeared in a recent Spectrum News story about how the garden is bringing national attention to Indigenous agriculture.

“The work of these students highlights the tremendous importance of food access and gardens for our campus community,” Jiménez-Soto says. “These gardens are hotspots of biodiversity and are so important as we address climate change, biodiversity loss, and food insecurity.”

Led by Pete’s Giving Garden faculty representative Chaya Lee Charles, Falk’s Nutrition and Food Studies Department also partners with the University’s Office of Sustainability Management, which oversees day-to-day operations of the garden and helped facilitate the agroecology lab for the Falk students.

“This is the first class from Falk that has really imbedded– yes, pun intended–the garden and Sustainability Management with students who are getting their hands in the dirt and using the garden as it was intended to be used as – a campus lab,” says Melissa Cadwell, the University’s sustainability coordinator.

“I hope that collaborations between Nutrition and Food Studies, Sustainability Management, and the Hendricks Chapel Food Pantry help reduce the stigma around asking for help,” Lopez says. “Students deserve a space that enables them to acquire food in a dignified way.”

To learn more about the agroecology class, we talked to three students: Michelle Tynan G’23, who’s from Olympia, Washington, and received her undergraduate degree in environmental studies from Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Oregon, in 2012; April Lopez G’23, a graduate assistant from Bridgeport, Washington, who received her undergraduate degree in business administration and communication studies from Gonzaga University in Spokane, Washington, in 2019; and Ryan Fitzgerald G’23, who’s from Sandy Hook, Connecticut, and received his undergraduate dual degree in biology and anthropology from SUNY Oswego in 2019. Here’s that discussion:

Q: Why are you taking the class and what are you learning in it?

Tynan: Agroecology is more than just the meeting of ecology and agriculture; it’s a theory of interconnectedness between living beings and a systems approach to understanding our surroundings. Our readings go beyond how to amend soil and grow healthy plants; they show us that it’s not possible to separate agriculture from social, economic, or political forces. It teaches us a “farmer first” approach–treating farmers as scientists with deep knowledge of their land and practices.

Much of the modern history of Western agriculture has been marred by the green revolution, corporate capture of the food system, and creating generations of agronomists who believe that short-term solutions (like pesticides, synthetic fertilizers, and fossil fuel reliant machinery) will solve problems like global hunger. Agroecology teaches us to zoom out and learn from ancestral knowledge of agricultural communities around the world.

Lopez: As someone with a limited ecology background, I was drawn to this course to gain a deeper understanding of the ecological foundation necessary to the study of agroecology. Drawing from my background in agricultural labor and my cultural roots has facilitated my understanding of agroecology and many of the sociopolitical topics (such as the conservation of traditional knowledge and Indigenous agrarian culture) that we discuss in class have resonated with my own experiences.

Fitzgerald: In our agroecology seminar we are learning the science, theory, and practice of integrating ecological systems thinking with agricultural environments, as well as ways in which industrial agriculture limits our vision of an affective, reciprocal agriculture (an agriculture that cares for people the same way that people care for it).

I’m taking the class because work on my thesis is undergirded by agroecological principles, but also because I want to familiarize myself with the topic more generally. I love gardening but I’m still a novice; the coursework and discussion is helpful for coloring my thumb green.

Q: What are you learning at Pete’s Giving Garden that you can’t learn in the classroom?

Lopez: Many classes in the Food Studies program tend to be theoretical, so they never require leaving the classroom. With a course like agroecology–a multi-pronged discipline that emphasizes the importance of Praxis–it’s important to have spaces where we can apply the concepts we are learning. Pete’s Giving Garden is a space that allows for a local and accessible understanding of agroecology.

Fitzgerald: Having the garden available to the class brings everything down to earth, literally. You can’t learn what soil smells like, how to plant onions, or the texture of the earth in a sterile lecture hall. You wouldn’t go to a doctor who has never seen a patient and only read the textbooks! Same with gardeners. There’s a reason they say never trust a skinny chef.

Tynan: Without a garden, we would not have access to a living agroecological lab. We can apply what we are reading about to what we can see, feel, and measure in the garden. For example, we learned how soils are healthier when there is a high level of species biodiversity present. We can then go to the garden and compare the soil in places where there is little species biodiversity to areas of the garden that have lots of different plants growing.

Q: Why is this topic–and by extension this class–important to you and your future career?

Fitzgerald: I hope to work in urban and community agriculture for a while in Syracuse. There is such a rich tradition of home gardens in this city, and I want to be part of a team that provides space for people to exert some agency in the food system instead of being dependent on massive supply chains and subject to the arbitrary, reactionary whims of a global marketplace. This class and its related topics touch on the need to have a robust, community-oriented food system that is environmentally and culturally attentive in its agrobiodiversity.

Tynan: I have experienced the dairy industry from many sides and feel strongly that dairy farmers and farmworkers deserve our utmost respect and support. I am currently on a multi-institution, USDA grant-funded project called “Coast-Cow-Consumer” that focuses on the benefits of feeding seaweed to dairy cattle to reduce their methane emissions. My role on the project, along with (Falk Family Endowed) Professor Rick Welsh, is to connect the seaweed, greenhouse gas, and animal science occurring within the project to the reality of the dairy industry.

We use a “farmer-first” methodology, interviewing farmers and dairy nutritionists about why they do or do not feed seaweeds, what benefits they observe, and what would help them implement seaweed supplements on a regular basis. Agroecology teaches us that excluding farmers from agricultural studies is a mistake and misses out on cocreation and sharing of knowledge–a core tenet of agroecology–as well as opportunities to approach agricultural issues from a socio-economic viewpoint.

My goal after graduating is to find meaningful work that improves rural livelihoods, including farmers, farmworkers, livestock, and the surrounding ecosystems.

Lopez: Food studies, despite sounding incredibly narrow, is a broad discipline. I was interested in food studies primarily to do work related to labor and food security, but I believe for me to approach a career in food I should look at the whole system. Agroecology’s principles are fundamental to developing systems-thinking that will inform how I practice food justice going forward.

Q: What would you say to prospective Nutrition and Food Studies graduate students about taking this class?

Tynan: This is a foundational course for reframing our understanding of agriculture. It is not possible to fully understand our food system without learning how food is grown, and how it can be produced more equitably. I also think the opportunities this class has provided for hands-on learning are unique. Most of our other core courses are reading and writing heavy and provide a strong foundation for food studies, but this class gets us outdoors and out of the campus community. Visiting farms and learning from farmers about issues they face and visiting the Syracuse garden and getting our hands dirty provides opportunities to engage with the material in an embodied way.

Lopez: As people, we play a major role in our food system. We are not separate from the system and as participants, the more we know, the more appropriate actions we can take in improving and sustaining our food system. Prospective students interested in learning more about the food system broadly should take a course like agroecology to gain a more holistic understanding.

Fitzgerald: It’s a great crowd of people, and it really demystifies deeply embedded conceptions of the food system. In this program, you learn to “stay with the trouble,” as Donna Haraway puts it (said like a true academic!). As for the agroecology class, get your hands dirty, but also be prepared to say that gardening isn’t for you. Just because you might hate dirt, or laboring in the hot sun, or bugs, or worms, or waiting months for harvest, doesn’t mean that you will be disconnected from these beings or systems. If that revelation comes to you, there’s plenty of space in the food system to accommodate you.

Food Storyteller

Located near the heart of Haudenosaunee territory, Syracuse University is committed to empowering and supporting Indigenous students of any tribe or nation. From academic programs and resources to welcoming and supportive communities, Syracuse University provides a campus community with faculty, staff and alumni who are invested in helping Indigenous students succeed—like these students and alumni who call the University home.

On campus last summer, Ethan Tyo ’17, G’22 started a garden featuring the Three Sisters—corn, beans and squash—to honor the traditions and culture of the Onondaga Nation, firekeepers of the Haudenosaunee, the Indigenous people on whose ancestral lands Syracuse University now stands.

For Tyo—a food studies master’s student in Falk College who recently published the cookbook Fetagetaboutit—the garden, a cultural installation located in Pete’s Giving Garden on South Campus, represented a way to bring Native American students together and to thank the campus community for its support when he was an undergraduate majoring in information management and technology in the School of Information Studies.

The Three Sisters are the foundational foods of the Haudenosaunee people, and their growth from seeds embodies progress toward recognizing the contributions of Indigenous peoples, Tyo explains. Tyo, who’s Akwesasne Mohawk, wolf clan, used the traditional planting methods of the Onondaga Nation in creating the garden, which is part of his graduate practicum. The garden is being kept for seeds and extra will be given back to the Nation as a reciprocal gift and to acknowledge the important work they have contributed to the University community.

“Indigenous students need people to come together and understand projects like this,” Tyo says. “I’m happy to see how much the school has adopted the garden and given us these opportunities.”

Diane Lyden Murphy Concluding Tenure as Dean

A longtime member of the Orange community, Diane Lyden Murphy ’67, G’76, G’78, G’83, dean of the David B. Falk College of Sport and Human Dynamics, has had an impactful, accomplished career at Syracuse University—as a student, faculty member and academic leader. Today, Murphy announced her plans to conclude her tenure as dean at the end of the academic year in 2023. A search for her successor will begin in January 2023.

“Diane has been a force of nature at Syracuse University since she arrived on campus nearly 60 years ago,” says Chancellor Kent Syverud. “She’s an innovator who inspires and engages others in transformational initiatives. Through her work in sexual and relationship violence, gender equality, diversity, inclusion and accessibility, Diane has both enhanced the student experience and helped our Orange community become a more welcoming place for students, staff and faculty.”

“In the years I’ve been at Syracuse University, I’ve been incredibly impressed with Diane’s work,” says Vice Chancellor, Provost and Chief Academic Officer Gretchen Ritter. “As a fierce advocate for her college and some of the University’s most important initiatives, she has an extraordinary ability to communicate with and engage others in what is truly important to the University experience. She is highly respected and for good reason because she is a person of high integrity.”

Murphy says serving her alma mater all these years, especially in her most recent role as Falk College dean, has been the honor of a lifetime.

“It has been an extraordinary privilege to be able to integrate my life’s work and focus as an activist scholar, social worker and social policy faculty with a career that articulates this effort in many ways over the years,” Murphy says. “I have built a cherished network of friends and colleagues that focus on matters of social justice and progressive peace work for both the community and the university, and together we have moved these communities forward.”

Appointed as dean of the College of Human Services and Health Professions in 2005, Murphy expanded that college with the Department of Sport Management to create the David B. Falk College of Sport and Human Dynamics in 2011. Murphy led a successful effort to integrate these disparate but complimentary curricula into one college, which moved into the White Hall-McNaughton Hall complex in 2015, physically bringing their departments together for the first time.

In addition to forging and shaping the Falk College, Murphy established a college Research Center and launched new undergraduate majors and minors, and several graduate programs. Her commitment to global education has resulted in study abroad opportunities throughout the Falk College. Her dedication to accessibility and global outreach led to groundbreaking new online programs, including online graduate programs in social work and marriage and family therapy. She helped create the food studies and sport management majors; launched the nation’s first bachelor’s degree in sport analytics; and integrated the Department of Exercise Science into the college. Murphy also led the creation of Falk’s Department of Public Health, and spearheaded collaborations with other colleges, including the School of Education, the College of Law and the Martin J. Whitman School of Management.

Mission-driven and passionate about issues of equality, diversity, inclusion and accessibility, Murphy believes that progress results from collective wisdom and collective action.

“We’ve learned a lot from the Haudenosaunee women, the Native women who have always led and been a very important voice, but their men lead with them,” says Murphy. “It’s about empowering people, getting people to the table, because collective voices make the best decisions. You need to have people who have different life experiences because they will think about things you wouldn’t have thought about.”

Murphy applied this passion to several critical leadership roles on campus. In August of 2021, she was one of a three-person interim leadership team appointed by Chancellor Syverud to advance the University’s diversity, equity, inclusion and accessibility (DEIA) priorities and strategic planning efforts. Murphy also serves as co-chair of the Chancellor’s Task Force on Sexual and Relationship Violence, a role she’s held since 2017. And, during former Chancellor Kenneth A. Shaw’s tenure, she served as a consultant to him on women’s issues while director of women’s studies. In that role she co-founded the University Senate Committee on Women’s Issues while also co-writing the University’s first Sexual Harassment Policy, Domestic Partnership Policies, Adoption Policies and Gender Equity Studies with the goal of elevating Syracuse’s commitment to a family friendly environment.

Murphy is a four-time Orange alumna. She earned a bachelor’s degree in sociology, a master of social work degree, a master’s degree in social science and a Ph.D. in interdisciplinary social science, all from Syracuse University. She became a member of the University’s social work faculty in 1978 and also served as director of the women’s studies program in the College of Arts and Sciences from 1989-2005, where it became a department with tenured faculty scholars and built the first B.A. and certificate in women’s studies at Syracuse University. She has also served as an elected faculty member of the Syracuse University Senate since 1980.

A Recipe for Food Justice

Ever since Ashia Aubourg ’18 was a child, she dreamed of one day working as a chef. Food was always the epicenter of her life, and from an early age, Aubourg would help her family in the kitchen, even whipping up side dishes for Thanksgiving.

Aubourg admits she had career tunnel vision and was focused on becoming a chef…but as she readily admits now, life never goes according to plan. So it was during an internship in high school that Aubourg first realized just how big of a problem food justice was in this country, and that she wanted to dedicate her career to addressing these inequalities.

“It was really cool that I was working in this restaurant, but no one in my family can afford to ever come and eat here. None of my friends and none of the members of the community, even though it was nestled within our community, could afford to come and enjoy these delicious foods that we offered. That just got me thinking about what food inequality and food justice looks like. Here I had this super tunnel vision of going down this culinary path of wanting to become a chef, but the culinary curriculum was very much focused on the technique and history of food, but we never dug deep into the societal impact that food has on us,” Aubourg says.

Following a spontaneous and inspirational conversation with an admissions counselor from Syracuse University, Aubourg decided to become one of the first students enrolled in a new academic offering from Falk College, the College of Arts and Sciences and the Maxwell School: food studies and policy studies.

After earning dual bachelor’s degrees in food studies and policy studies in 2018, Aubourg launched her career as a food justice advocate, entrepreneur, journalist, podcaster and creator of healthy recipes. Today, she serves as the global culinary program lead for the San Francisco, California-based company, Asana, empowering communities through the power of food.

Aubourg discusses food justice and food insecurity and how these issues affect millions of Americans; how food plays an important role when it comes to social justice, healing and culture; why food is about more than nourishment; and how her time at Syracuse University helped fuel her passions while encouraging her to take advantage of every opportunity.

’Cuse Conversations with Ashia Aubourg

Hello and welcome back to The ‘Cuse Conversations Podcast. I’m John Boccacino, senior internal communications specialist at Syracuse University.

Ashia Aubourg:

It’s one of those issues that it’s like, it literally can touch every social impact issue we have going on. If we’re thinking about education inequity, food ties to that. If we’re thinking about environmental issues, food ties to that. If we’re thinking about political issues, food ties to… It really is one of those intersectional pieces. And for me, it was just really important to be in an academic space that was using food as sort of the epicenter or the lens to then discuss all of these issues that we’re dealing with as a country.

John Boccacino:

Our guest today on the podcast is Ashia Aubourg, who earned a dual bachelor’s degrees in food studies from Falk College and also in policy studies from the College of Arts and Sciences in 2018. Ashia is a dedicated food justice advocate, a journalist, a podcaster, an entrepreneur, and a creator of some pretty tasty recipes, if I may say so myself. She serves as the global culinary program lead for Asana based in San Francisco. And Ashia is kind enough to join us here for this episode of the ‘Cuse Conversations Podcast, diving into all issues related to food justice. Ashia, how are you holding up these days?

Ashia Aubourg:

I’m doing good. Can’t complain. Excited to be on this podcast to kind of just talk through my journey and how Syracuse really influenced a lot of it.

John Boccacino:

Ashia was always interested, always passionate about food from an early age, but didn’t want to take the traditional route with food. Pick up the story from there. How did you become so interested in food? What was that relationship from an early age?

Ashia Aubourg:

Love this question. I feel like that’s the question I love when I’m applying for a job. I’m like, “Ask me that question, that’s what I want to answer.” Because my path is very just untraditional. So growing up, my family, let’s just start there, food was the epicenter of our culture. When we have gatherings, food is always present. When we’re unfortunately taking time to honor just like unfortunate events that have happened in our lives, food is always present. Comfort wise, food is always there to really kind of just bond us together. So just from my early ages of growing up, food has always just been the epicenter of my life.

Different cultural recipes. So my grandparents immigrated from Haiti, so a lot of Haitian cuisine. But also just, I love to say my family’s kind of this melting pot of culture. So whether it’s Ethiopian food, Puerto Rican food, Dominican food, Haitian food, other types of Caribbean foods, we always had all of these beautiful cultures present at our table for different holidays and family gatherings.

I just naturally grew up wanting to be a chef. My family was very supportive of this at an early age. I know typically a lot of people that grew up wanting to be chefs typically get a lot of backlash from family members just because it’s a pretty cutthroat career. But no, my family was very much onboard. I was very young, cooking in the kitchen from a very young age. I was assigned Thanksgiving dinner, like side dishes, so I was always in the mixed cooking.

Essentially, in high school, I went to a vocational high school that had this vocational program, so They had a culinary arts program. And essentially, throughout my four years in high school, I participated in this program, was pretty set on becoming a pastry chef. I ended up, when I was 16, working for James Beard award-winning restaurant, interning for their pastry chef. I was like dead set on going to the CIA, for those that don’t know the Culinary Institute of America. I was very much tunnel vision on this path towards becoming a chef.

But as we know, life never goes as we plan, and I think that’s really just the theme of my story. Essentially, when I was in high school, as I was working at this super, super fancy, again, James Beard award-winning restaurant, I started to kind of just witness what it felt like just this weird nuance, something just feeling wrong or not right. And essentially, I was just like, “It’s pretty cool that I’m working at this restaurant,” right, “but no one in my family can afford to ever come and eat here. None of my friends, community members, even though it was nestled within our community, can afford to actually come and enjoy these delicious foods that we have offering.”

So kind of just got me thinking just a lot about like what does inequities look like in the food system and just from a baseline of access to food. So essentially, it just got me thinking a lot because I’m here, I am just super tunnel vision in this culinary path wanting to be a chef. The culinary curriculum was very much focused on the technique, right, or just the history of food, but we never dug deep into socially how does food impact us, right?

And at the same time that I was having all of these questions, I started to just naturally like I love inquiry. I started to ask a lot of these questions in my courses at my school and things like that. And one of my professors was like, “Let me connect you to this woman. Essentially she started a program here in Cambridge, Massachusetts,” which is where I’m from, “and essentially what the program is that she gets all of these volunteers to essentially packed lunches for students in the K-8 elementary school system in Cambridge to give them free lunch on the weekends.” And I was like, “This is super cool,” because the root of that was that a lot of public school students depend on the free school breakfast and free school lunch in order to get their main nutrition for the week. But on the weekends, of course, without that being present, unfortunately, a lot of people that are food insecure can deal with not having food present.

So I was just immediately in love with just the mission of her volunteer project. And me, of course, being the very passionate and motivated person that I was at 16, I emailed her and I was just like, “Are you looking for interns? I would love to work with you and love to learn from you.” And essentially that kind of just like I always say when it comes to the food justice or overall food policy field, it’s very small. So once you get plugged into, it’s kind of just this array of just awesome people you meet and also just this array of opportunities that then present itself.

That’s when it came down to this pivotal decision I had to make when I began applying to colleges because I was so set on going to a culinary school. But then after getting these experiences of working on the ground of community members and working on these really vast issues that we had going on, I really had to sit with myself and be like, “Is working in a kitchen really what like? Is that really what I want, or is it something else?” And write food studies was not a popular major then. It wasn’t even a major at Syracuse when I considered Syracuse.

But eventually, long story short, I decided to going into some type of nutrition or public health program because it kind of seemed aligned. So I started looking for schools that had cool programs that I was interested within that realm. And I will never forget, Syracuse was always one of my top schools just because I had known people that went there. My Aunt Diana had graduated from Syracuse and just had a very amazing career after working at Syracuse. So for me, I had always had this connection to Syracuse for a very long time. And essentially, I’ll never forget I applied and while I was waiting for my application to go through, they did these in-person interviews and they had came to Boston to do these interviews. To my mom, I was like, “We have to go.”

So for the most part, most of the colleges I was applying for, I wasn’t doing the in-person interviews, it was pretty much just the typical application. But there was just something tying me to Syracuse and I was like, “We have to go.” If I remember, I’m just talking about what I’m interested in, what I’m passionate about. And the woman that was interviewing just cut me off and she was just like, “Wait.” So she was like, “You’re interested in food. You’re interested in social justice policy,” blah blah, blah, blah, the environment, like all these things. She was like, “Okay,” I know this is going to sound weird, but she was like, “They’re thinking of making this new major at Syracuse called food studies.” It’s not a major yet, but she was like, “I promise you, just apply into nutrition or public health and by the end of your freshman or sophomore year, it’ll probably be a major.”

So then again, it was another one of these moments where I was like, “Okay, this isn’t really firm. I have to trust this woman that I literally met for 30 minutes. But okay, let’s just go for it. Let’s hope that it works out.” And essentially, I ended up going back into my application and being like, “I’m very interested in the food studies program that they’re hoping to create.” And then essentially, from there, I remember I ended up getting the acceptance and then a lot of the food studies faculty that had got hired on ended up reaching out to me because they were super excited that they had this one person that was interested in the major. And then I think actually within two months of me being at Syracuse, I was enrolled into that major. But that’s essentially how I got to Syracuse.

John Boccacino:

I love finding out people’s how and the why and how you connect the dots with your passion out there and we have a lot to unpack in your response right there, but I want to start off with this kind of follow- up question. How big of an issue is it in our country right now the issues of food insecurity and food justice?

Ashia Aubourg:

I think it’s a huge issue, right? I think it’s a huge issue because it affects so much, right, from early adolescence. If we’re not getting the proper nutrients that we need, it can affect our development when we get into grade school and high school. Again, if we’re not getting the foods we need, and not just from a nutrition standpoint, but also from just a cultural and comfort standpoint, it could affect us in terms of being able to focus, unfortunately developing eating disorders or unhealthy relationships with food. And then continuing to move forward from I just to think about it from just the developments of people, but also just from an adult standpoint. If I don’t have access to foods that I feel connected to in my neighborhood or foods that I can afford, right, it’s just this spiral effect that at each level can have these terrible consequences.

And that’s just the food access piece, right? Then we also have the food policy piece, as it relates to a lot of the work that I typically worked with was around food stamps and SNAP. So really just like able to make sure that people can have access to the resources that they need in times of hardship or in times of just social inequity, right? So a lot of the work that I typically did as it related to food stamps was around these healthy incentive programs, so essentially allowing people to use their food stamps to then purchase foods from farmer’s markets. Because I think, of course, there’s just a lot of just terrible rhetoric around the food stamps program in general, the people that use it, what they typically want to buy. And from a lot of the work that I was doing, unfortunately a lot of the cultural vegetables or foods or grains, things like that were just not accessible for people. So a lot of the work that I did around policy was around promoting these programs to make this benefit more accessible to people.

And then we have the whole environmental aspect, right. And people can talk for hours about how different aspects of just the way that we approach policy as it relates to just the way we produce food, the way we properly disposed or waste food can impact our environment just terribly. So I think it’s one of those issues that it’s like it literally can touch every social impact issue we have going on. If we’re thinking about education inequity, food ties to that. If we’re thinking about environmental issues, food ties to that. If we’re thinking about political issues, food ties to… It really is one of those intersectional pieces. And for me, it was just really important to be in an academic space that was using food as sort of the epicenter or the lens to then discuss all of these issues that we’re dealing with as a country. And then, of course, beyond the food access, another piece that I really focused on was just food and identity, so food and race, how that impacts us in terms of the racial issues that we have going on in this country.

John Boccacino:

It’s easy to think of food simply as a way to nourish your body.

Ashia Aubourg: Exactly.

John Boccacino:

But it’s so much more than that, and you hit on this with your most recent answer. How do you feel that food serves a really important role when it comes to justice, healing and our culture in this country?

Ashia Aubourg:

So I love that question because I think that’s what I always go back to for my why, right? If people ask like, “Why do you do this work? Why are you interested in this work?” And I think literally the aspect of food at a base level, right, is nourishment for us, which is why we could talk about it later. I called my blog Nourished Palate because I really genuinely believe that food serves so many purposes.

But back to your question, food really ties people together, right? But also food can also be weaponized, right, like we see in plenty of countries in times of war, just like serious conflict. Typically, the first thing to just strip people’s power away is removing their access to food. And, of course, we’d love to think about food, right, and that very dramatic way of being a way of stripping people’s power, stripping people’s dignity. But what I feel doesn’t always get recognized is that that’s happening so much across all of our communities. Not in a very blatant way, right, but because of all these societal factors that are kind of influencing different people and their life outcomes. It can be very difficult to gain access to food, which of course, if we think about our hierarchy of needs is definitely just one of the basic levels of needs, right?

So I would say food is definitely nourishment, but I also think it’s a form of power for people. I think it’s definitely one of those things that allows people to really have this dignified life. And with so many aspects of this getting stripped away from people, and not even just in the literal sense, but if we think about indigenous people. And literally their seed is getting like taken away from them or to be able to grow these cultural crops, things like that. If we think about a lot of immigrants that have to come to countries, literally cannot find certain ingredients that they used to cook with. I think these are all the big conversations that come up for me when I think about food as nourishment, but also what it means to not have access to that nourishment.

John Boccacino:

With your current role, I want to get a little insight from you about, again, your current role as global culinary program lead for Asana.

Ashia Aubourg: Yeah.

What is that job all about and how is this position helping to achieve those goals you talked about of combating food justice issues in our country?

So I recently joined Asana, which is a tech company, as their global culinary program lead. And essentially, my role is to work to establish these culinary programs across the company globally. So I’m working currently with programs that are getting set up in the US, in Canada, Japan, Australia, Europe, Singapore, like a bunch of different places. Essentially, this role wasn’t meant to be this food justice oriented role, which was actually a piece of my career that I was worried about. Because for so long all of the programs and projects that I’ve worked on in terms of working with different organizations have been heavily focused on it. But what I love to say is that, again, food is so intersectional. So you can essentially enter any food career path and essentially make it what you want in terms of being able to tackle justice.

And another aspect of food justice that’s very important to me is economic empowerment, especially for BIPOC-owned businesses and things like that that are operating in the food space. So essentially, what I’ve been working on in this role is really trying to help and mobilize small BIPOC-owned businesses to be able to get these high profile contracts with tech companies. So essentially, I’m working with different BIPOC-owned food businesses to be able to help train them, but also help get them set up with working as vendors to support the culinary programs for this tech company across the globe.

What that typically looks like, right, is really I feel like the first thing is typically their empowerment piece. Typically, I’ll do a lot of research of different BIPOC-owned food businesses that do corporate catering and things like that. And the first thing I’ll do is just reach out and be like, “Hey, I think that what you’re doing is great. Would you be interested in taking on bigger contracts,” which of course yields more revenue for these companies, well, not these companies, but these BIPOC-owned companies. And I feel typically the first response I get is I don’t have capacity to do it. I would love to do it, but I just can’t right now.

And I think what my role in this role has really been is like, “What can we do to help you get there? Is it training that you need? Is it funding for additional staff? Is it help with developing menus for the programs? What can I do in my role to help you get on board with being one of these vendors for our tech company?” And I feel like for me, that’s been pretty rewarding because a lot of the spaces in the food justice field that I’ve worked at have been on the, I feel like I think of different levels of the food justice field, but I feel a lot of the work that I’ve done in my previous roles has been around food access, right, so ensuring that people have access to food on just like a granular level. But then also food waste, ensuring that we’re not wasting food and things like that.

But I also think a really important piece of this is also just economic stability. I feel like for a lot of BIPOC communities that start businesses, it’s tremendously hard for a lot of reasons, right? And for me, I think that being able to put a lot of these BIPOC food companies in a position to gain these contracts.

And another piece that I really love about a lot of the BIPOC companies that I’m working with is that they all have some type of social impact piece connected to it. So I’m working with one company in Vancouver that’s a catering company, but half of their business in terms of where the profits for this business goes is directed to feeding homeless people in Vancouver and training people who are formally incarcerated to work for their catering company.

So for me, it feels like a ripple effect, right? It’s like, “Okay, how can we get these BIPOC-owned food company or food businesses, like these smaller ones, into a position to be able to get more revenue for their business and then in turn they end up helping the communities that they’re in or employing people from the communities that they’re in?”

So that’s essentially what I’ve been working on mainly with my role at Asana. But I know eventually we’re also hoping to do more work around really engaging BIPOC growers as well. So we don’t want to just purchase from BIPOC-owned food businesses, but we also want to ensure that the produce that we’re getting for our programs is from local farmers, things like that. So that’s essentially the next step for me once I’m done kind of ramping up a bunch of these smaller food businesses.

John Boccacino:

It seems like a really both a perfect fit and a logical next step in your career. And especially, I love the fact of investing in the community and helping the BIPOC businesses and farmers both invest in them and help the communities rise up by having the revenue then come in and goes back into the local community versus being outsourced right into a national company that you’re not going to see the return on the investment.

Ashia Aubourg: Exactly.

John Boccacino:

Whereas in these areas where there’s food deserts or food insecurity issues and food justice issues, it’s a self-sustaining economy at that point. It gives back and you’re reinvesting and the people that are really going to benefit from your work. I love that aspect. I also loved before Asana, you mentioned this briefly, but Nourished Palate, the blog, the RecipeHub, a really creative resource that you launched. And I loved your slogan: Cultivating palates, where food is love. How is food love? I love that phrase. How is food love and what really inspired you to create Nourished Palate in the first place?

Ashia Aubourg:

Yeah. I also just like, well, kind of what you said back to the other thing about refueling economies, because I think going back to the other question I think that’s another aspect. I feel like about food justice that sometimes gets ignored. Sometimes it’s like, “How can we make sure the food feed communities? How can we make sure that there’s resources?” But I think the other piece to that is that a lot of community members want these dignified pieces of work, right? They don’t want just emergency food technically always coming to their communities. They want jobs. They want opportunities for growth, right? And as we talk about Nourished Palate, I think for me, I became kind of a part of a space during my career where I felt growth wasn’t happening. I felt like I was really wanting to go further in terms of the way I’m passionate about food and things like that.

And it was really a time where I was like, “Okay, maybe it’s time to start my own thing,” right? It was really important for me to go through that because I think it kind of teaches you how difficult it is for black BIPOC in general like people to really get to the space to start a business, all the barriers that come with it, all of just like second guessing because of a lot of reasons that are aligned with it.

But essentially, I started Nourished Palate as a blog. This was during COVID where I think a lot of people had a little bit of downtime. I had been laid off from a role unfortunately, and it definitely was just a time of insecurity. And I was just like, “What can I do? How can I continue this path that I’m on?”

So I first just started with posting recipes, right? Because again, going back to food is love, I was like, “But not everybody can cook. So how can I make this thing that I love so much accessible to different people?” So I was like, “Okay, recipes. Let’s connect it to social media. Let’s meet people where they are.” So I made an Instagram page. So I’m posting. First, I’m like I need to capture people, right? So I’m posting all of these mouthwatering pictures of food and I’m like, “If you want to make this, head to the blog for the recipe.”

So it started off just very base level. But I think for me, I was like, “I just want to build a community,” right. Like, “How many people have this connection to food and want to kind of bond over it during this time of crisis,” right, when COVID was peaking. Essentially, a lot of people were getting laid off. Unfortunately, it’s just a really difficult time of insecurity and also just like, “Oh, what’s going on in the world?”

So I started doing that. It started to receive a lot of attention just because I think everyone was in this space where I was like, “Okay, food is so baseline,” right? I always say like, “If you want to connect with someone, take them out to eat. Cook them a meal.” Because I think that’s one of the best ways to show your culture or receive someone else’s culture and kind of understand who they are as people. So again, started it as doing the recipes, doing the blog.

But then I was like, “Okay, this is really cool.” Starting to receive a lot of just people wanting to have dialogue. So then I was like, “Okay, maybe we can just start a podcast out of this.” So I was like, “But who do I want on the podcast,” right? I love Chefs to Death. But I was like, “This is not about a cooking technique,” right? I want to get deeper about food. So I started tapping into different people in the food justice industry, food justice realm to just interview them like, “How did you get to this space? What is it that you’re passionate about? And what’s a broad message that you’d want like a broader audience to know?”

And again, I think people just really connected with this idea of just opening up a space for different dialogue. And I was very intentional, too. I really wanted to showcase black women and black people that were in the food justice space in the work that they’re doing. Because I feel unfortunately, especially then I think a lot changed when unfortunately everything happened with George Floyd.

But there was a huge period of time in the media where a lot of black food creators, a lot of black people that were doing food justice work were just not getting media coverage. And I’m like, “There are these crazy stories of all of this amazing stuff that people are doing. Why isn’t Bon Appetit writing about this? Why aren’t these big food publications taking this stuff seriously?” Again, I think a lot of that changed when everything with George Floyd and the protest happened, right? But there was a very much a dry spell of coverage in the media for black women and black people in food.

Essentially, I continued with this theme of food is love, so continuing to try to offer just resources that were uplifting that in this time of just serious insecurity for a lot of people that could help them take their mind off of everything going on. And I continued with that, of course, things of COVID began to kind of level out a bit. I don’t think we’ll ever be at a great place of COVID, but they began to level out. And I was like, “Okay, people are starting to go back outside, right? I can’t continue just doing this work from the blog standpoint. I can, but I don’t think it’s going to gain as much traction.”

So then I was like, “Okay, I had already had gotten my LLC,” and I was like, “But how can I push the boundaries even further?” And I was like, “Okay, maybe we should actually just start a business.” So I ended up getting something called a cottage license, which a lot of cities have that essentially allows you to be able to cook food from your home without having to pay rent at a kitchen commissary or something like that to then sell that food at farmer’s markets. So essentially I started a farmer’s market business selling Caribbean-inspired baked goods and drinks.

And I’m going to be completely honest with you. That was the most difficult time of my life. I think people really underestimate what it takes for small businesses to be able to get their grounds running. And I think that’s even amplified for people that come from families that have never been business owners, right? I think that’s even amplified for people that are immigrants and can’t understand all of the legal jargon when having to apply for different certifications, LLCs, things like that. So essentially, I had figured it out, right, but it was not easy. But I did figure out all the logistical aspects to get my business running.

John Boccacino:

You have had, I’m just marveling here with the fascinating journey you’ve taken and from someone who thought they knew what they wanted to do to evolving your career and adapting and adjusting and still having an impact in the community and focusing on the greater good. It’s commendable how you’ve taken this passion and made it a sustaining and worthwhile career. When you reflect back on Syracuse and the role that Syracuse University played, what are some of the biggest lessons you learned from your time here at Syracuse that have inspired and influenced your career?

Ashia Aubourg:

I would say the first thing is just marveling at opportunity and understanding that you don’t have to be put in a box. So I think when I got to Syracuse I was like, “Okay, I have this major. I have to stick in this major. All the clubs I joined have to be related to this major. That’s what we’re going to do.” All the internships I do have to be related to this major. That’s what I thought Syracuse is going to be like.

When I got there, it was a completely different scenario. It was like, “Whoa,” there’s all these clubs. Even if it’s not tied to what I’m studying, I can join them. I did an internship in New York City for a semester when I was at Syracuse, teaching at a public school, which was completely unrelated to food, but an opportunity that Syracuse allowed me to go on. And I think having just so many opportunities to step outside of my bubble and just explore other passions was really important for me and just taught me the skill that I’ve carried throughout life.

If you look at my resume, if you look at my background, it is so diverse. Yes, I’ve done work mobilizing farmers, right? I’ve done work working for food waste organizations. I’ve done work working for food policy organizations. But I’ve also done work working for magazines, writing articles, doing podcasts. I’ve also done work like communications, working for different companies and things like that. And I think for me, learning that so early in college that although I have this passion and this skill set that I’m trying to develop doesn’t mean that I can’t jump into other fields or other avenues of work was just very important for me to learn very early on.

And it was so funny, when my friends reflect on my time from Syracuse. They’re like, “Were you even at Syracuse?” Because I was always doing something. So my sophomore year, my sophomore spring semester, I was in New York City for the semester teaching. My junior year semester, spring semester, I was in Italy doing the whole food program. So I was just always in the mix doing something when I was at Syracuse.

But I think it was just very important for me to just learn very early that it’s like we have this whole world, right? We have this whole life ahead of us. I feel like very traditionally, at least in my family. People typically stuck with whatever field they were in for the rest of their lives. And I think for me it was just pretty liberating to learn that like, “No, there’s so many opportunities out there. Dip into this, dip into that,” and kind of just see where you’re at.

And granted, I graduated in 2018. So I’m still pretty early in my career, but I think I’ve definitely been taking these couple of years after college to really just take the time to explore what is it that I’m genuinely interested in and that can change. And I think that’s kind of what I’ve been seeing so far in terms of what I’ve been doing. Really, just trying to explore before I settle and pick on something and pursue that for the rest of my life.

And luckily, when it comes to food, I remember all of my food studies professors, first of all, all amazing and I feel like that’s rare. You know in college, there’s always that one professor that you’re like, “Oh, didn’t work out for whatever reason.” No, the food studies program, I was just always so amazed and always felt so supported by all of the professors. And I think one of the biggest pieces of advice that I took from them and a lot of their wisdom was like, “You can take this degree and apply it to anything. You don’t have to just go and work for a nonprofit doing food justice work. You can go and work for McDonald’s and try to help change their sourcing techniques.”

Pretty much I feel like they really instilled into me that this degree is what you’re going to make of it, right? We’re going to give you the tools, the resources, try to help you feel supported, but it’s ultimately we’re kind of encouraging you to explore and see how you can take this work that you’ve been doing into other spaces.

John Boccacino:

What does it mean to you to be a Syracuse University graduate?

Ashia Aubourg:

I think for me personally, this might not be the typical answer that you get to this question. So my Aunt Diana Aubourg graduated from Syracuse. Unfortunately, she passed away from breast cancer a couple of years ago. Actually. The freshman year that I started at Syracuse, she passed away. She had a very similar experience to me, was just so involved at Syracuse in so many programs and that was kind of just the kick starter for her career. She ended up going into work, to do work with people in Africa, around various like NGO projects, just a lot of really, really important work.

So for me, being a graduate of Syracuse University really felt like how can I continue on this legacy of my Aunt Diana who went to Syracuse and just squeeze so much out of her experience. So I have a lot of pride in going to Syracuse mainly because I saw what it did for my aunt, right, and I also saw what it did for me. So I really just am so thankful for my experience and just almost for me the generations of opportunities that it’s allowed just for me and my family.

John Boccacino:

She is Ashia Aubourg. She’s going to continue to do great work in the line of food studies and food justice, and we wish you nothing but the best. Keep up the great work and thanks for stopping by the podcast today.

Ashia Aubourg:

Thank you. I really appreciate that. Thank you.

John Boccacino:

Thanks for checking out the latest installment of The ‘Cuse Conversations Podcast. My name is John Boccacino, signing off for The ‘Cuse Conversations Podcast.

Transcript by Rev.com

Creating a Sustainable Food System

“In order to have a truly sustainable food system, both locally and globally, I argue food labor, and relatedly, racial justice and immigration policy, must be central to our understanding of how to change the food system,” says Minkoff-Zern, the Food Studies graduate director.

“In addition to addressing working conditions on farms and other parts of the food chain, food systems scholars and practitioners–and really anyone who eats–can and should be looking to the people who do the work to maintain our food system everyday as holders of knowledge and leaders in making the changes themselves,” she adds.

Minkoff-Zern, an affiliated faculty member in the departments of Geography in the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs and Women’s and Gender Studies in the College of Arts and Sciences, has concentrated much of her research on immigrant farmers. Her 2019 book, “The New American Farmer: Immigration, Race, and the Struggle for Sustainability,” offered new perspectives on racial inequity and sustainable farming.

We asked Minkoff-Zern to explain her recent research, how food security and immigration are related, and why what happens to farm workers matters to you and me. Here’s that conversation:

Q: Can you summarize the focus of your research and the subsequent articles published in the “Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development” and the “Journal of Rural Studies?”

A: This research project looks at the federal H-2A Temporary Agricultural Workers program and how it functions on the ground. This program is essentially a work visa program for farmworkers who come to the U.S. primarily from Mexico and Caribbean and work for up to 10 months before they are required to return to their home country.

Our team at Syracuse worked with the Cornell Farmworker Program to better understand the conditions for both workers and farmers engaged in the program, with a focus on mid-sized farms. This was a mixed methods project, where we utilized interviews with farmers, workers, and intermediary agents; U.S. Department of Labor data; and media sources for our analysis. This study is one of the first to look at the work and usage conditions on small- to medium-size farms using this rapidly growing farm labor program.

Q: What stood out to you during your research?

A: We found that the program is challenging for mid-size farmers and problematic for workers. Yet it is often promoted as a bi-partisan, farmer-friendly, and worker-approved approach to address the lack of experienced and willing farm labor in the U.S.

Politicians, media, and lobbying organizations that promote the H-2A program assume it functions the same at all farm scales, ignoring the lack of resources on small- and medium-size farms to manage and pay for the additional human resources, paperwork, and requirements to use the program. For workers, the program provides a legal entry to the U.S. but mostly limits them to one farm/employer, making it difficult to speak up if things are not safe or fair at work.

The program also overlooks experienced undocumented workers, who have been working for low wages and under difficult conditions in U.S. agriculture for decades yet are unable to apply for these jobs and gain the potential benefits of the program.

Q: What conclusions did you draw?

A: We found that the program is not designed to support the small and middle-sized farmers who grow seasonally available fresh food, nor does it provide a just option for farmworkers. Yet, despite their critique, most farmers do say they still want access to the program, due to lack of better options.

Ultimately, this program and the related bill (Farm Workforce Modernization Act) are Band-Aid solutions to a much broader structural problem: producers and laborers in the food system get a smaller percentage of the food dollar, and workers operate within a broken immigration system, forcing them to settle for highly problematic employment options.

Q: The Farm Workforce Modernization Act, which has been passed by the House but not yet by Congress, involves changes to the H-2A program. Can you explain the changes that have been proposed?

A: Although this program generally has made up a small portion of the overall agricultural workforce since its inception in 1952, program usage tripled over the past seven years. This growing popularity has prompted heated debates about potential reforms, most recently regarding the Farm Workforce Modernization Act.

If this bill were to pass, the H-2A program would be expanded to include year-round agricultural industries, provide a pathway to citizenship for some workers, and temporarily cap the potential for wage increases for workers. It would also force the e-verify system on all agricultural producers, which checks the documentation status of workers. If passed, this would leave a large majority of the experienced farmworkers in the industry out of a job, pushing farmers into using the controversial H-2A program.

Q: What changes would you recommend based on your research?

A: There are no silver-bullet solutions to the problem of farm labor in the U.S. today. As fewer people in the U.S. grow up in rural areas and on farms, we lack an experienced, domestically born workforce. Additionally, farm labor has a long-rooted history in racial exploitation and relatedly, low wages and poor conditions.

To create a sustainable food system for both workers and farmers, the U.S. needs a more comprehensive agricultural immigration reform strategy, which includes workers that are already in the U.S. working in agriculture and allows for upward mobility for farmworkers.

Farmworkers come to the U.S. with agricultural knowledge and skills, including sustainable practices and how to grow biodiverse food systems. Instead of relegating them to a migrating labor force, a better program would help provide current workers–most of whom are not currently authorized to work in the U.S.–legal access to work and citizenship, so they can live and work without fear. This would also help farm owners, who would not have to fear losing their workforce to an immigration raid and avoid the expensive and bureaucratic process of working with the H-2A program.

Q: What can be done to connect your research and recommendations to the lawmakers who are making the decisions?

A: As I mentioned, this project was a partnership with The Cornell Farmworker Program and its director, Mary Jo Dudley. The Cornell Farmworker Program works to disseminate research projects such as ours to a broader policy making and practitioner audience. We are still working on publishing our third article from this research, and plan to make more formal recommendations to policy makers as all our findings become public.

Q: Why should people care about what happens with the Farm Workforce Modernization Act and the H-2A program? How does it impact our everyday lives?

A: Anyone that cares about access to fresh and healthy food should care about farm labor and related immigration policy. Farmworkers do the labor every day to bring food to our plates. Without a functioning system to justly and safely support workers on a regional and national scale, we risk a food system more vulnerable to climatic shifts and global upheaval.

Q: You worked closely with Food Studies graduate students on your recent research. Can you describe the perspectives they brought to this work?

A: Both Anna Zoodsma G’22 and Michelle Tynan G’23 have been essential to the research on this project and are co-authors on the papers. Students bring unique perspectives, based on their own professional experience, when looking at interview data, literature, and media.

For example, Michelle worked at the USDA (United States Department of Agriculture) before starting graduate school in Food Studies, and Anna was doing practicum work on a local project with refugee farmers. Anna took the lead in conducting the media analysis and was the first author on our most policy relevant paper recently published in the “Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development.”

Committed to Student Success

As a non-traditional, first-generation undergraduate student at Syracuse University, Chandice Haste-Jackson excelled academically but always felt there was something missing in her pursuit of knowledge.

That missing piece? Connecting with others.

“Ultimately, I discovered that in connecting with others, I could expand my knowledge and understanding beyond anything I learned from textbooks,” Haste-Jackson says. “That set me on a career journey oriented toward human connection, holistic development, and service, whether that be in fields of teaching, counseling, leadership, or administration.”

This past summer, Haste-Jackson’s lifelong journey of connecting with others continued with her appointment as Associate Dean of the Office of Student Services in Falk College. An associate teaching professor in Falk’s Department of Human Development and Family Science (HDFS), Haste-Jackson previously held several prominent HDFS positions and was chair of the Dean’s Committee on Diversity and Inclusion. In 2021-22, Haste-Jackson served as Syracuse University’s interim director of the First-Year Seminar course.

Before joining Syracuse University, Haste-Jackson was drawn to work that supported vulnerable populations. It was her job, she says, to help those populations expand their understanding, move from deficit toward sufficiency, and identify what wholeness, health, and stability meant to them and/or their families.

“Was this difficult work at times? Yes!” Haste-Jackson says. “But what I gained from these experiences is that our humanity connects us all, even those who are not like ourselves. We all want similar things–health, happiness, longevity, stability–and that makes us more interconnected than we think we are.”

To introduce Haste-Jackson to Falk students, we asked her to discuss her previous experience with students, the services offered by the Office of Student services, and questions that students might ask. Here’s that conversation:

What attracted you to your new job and why is it important that you’re helping Falk College students succeed?

After 20 years of working in nonprofit organizations and schools, rising through the ranks of direct service to executive leadership and administration, I spent a good deal of time teaching and training frontline employees and college student interns. In working with college student interns, I developed a desire to teach, mentor, and prepare the next generation of human service workers, a field that is very broad but one that involves human connection, holistic development, and service–tenets I live my life by!

Given the climate in which we live in today, college students are dealing with issues that may impact their ability to successfully engage in academic pursuits. The COVID-19 pandemic, mass racial violence, wars, and significant personal losses have impacted academic performance and emotional well-being. Helping students to navigate these challenges during their time with us in Falk College is what I endeavor to do, and I am committed to leading and supporting the professional staff in our office who have made that same commitment to student success.

I’m a first-year or transfer student who isn’t familiar with the Office of Student Services. What are the services you provide?